Contents

Editor’s note: Tanya Koshy is a product management consultant with deep experience at major tech firms. In part one of her two-part article, she described her process for understanding customer needs. In this second part, she describes how to use that information to align product teams and their business stakeholders.

Summary

Product teams and their business stakeholders often lack a shared understanding of customer needs, leading to organizational strife and failed products. I create a shared understanding through the careful use of customer evidence. I’ve fine-tuned my approach over my career leading product and growth teams at places like Google, Facebook, Groupon, and UserTesting, and with my consulting clients today. I want to share my core strategies with you– this is part two of my playbook.

The problem: lack of shared understanding

“The product launched…it’s something that no one wants or needs. We didn’t know it was happening. We can’t even sell it in some markets, due to the regulatory environment. It really deteriorates our trust in the Product team.”

– Sales Leader, Fortune 500 company

When I was working with a Fortune 500 company to help incorporate customer insights and data into their product processes, I repeatedly heard stories like the one above. I interviewed product core team members (product managers, engineers, designers, UX researchers) and their business stakeholders (marketing, sales, support) to understand their day-to-day processes and needs around building and launching products. A duality emerged from my interviews:

- Business leaders often felt blindsided by product launches, and were not convinced that these products were particularly valuable to the customers they worked with day-to-day.

- Product teams felt frustrated and obstructed by the business leaders’ seemingly last-minute objections to product launches.

This tension between product and business teams is not unique to a single company. Almost every team I’ve been on during my 15yr+ product career has started with a significant level of friction and animosity between the product and business groups, like that described above. The result is failed launches and severely demotivated teams. Also, sadly in my experience, when product leaders get fired, product-business dysfunction is often a key contributor to that leader’s perceived failure.

The failure of product and business teams to align around a shared understanding of customer needs is an existential threat to the success of products, teams, and careers.

A technology product is made real and successful by the combined efforts of a large number of people, each with their own functional expertise, perspective, and goals. It starts with the cross-functional core team building a product and then extends to the business teams selling, marketing, and supporting that product. But product core teams get so focused on the time-consuming, day-to-day work of shipping code that they can easily underestimate the importance of marketing, selling, and supporting the resulting products. And so, I always remind the product teams I lead, “For our customers, our product isn’t just the pixels we deliver to the screen, it’s the whole experience of how that product is marketed, sold, supported, and used every day.”

Also, if the product and business teams validating, designing, building, marketing, selling, and supporting the product aren’t all on the same page about what’s being built and its value to the customer, disaster ensues:

- People start to severely second-guess what they’re doing:

- “What is this? I don’t think our customers will use/buy it.”

- “Why are we working on this? Why don’t we work on X instead?”

- People become disconnected and demoralized, and work may slow down or stop.

- Hearing about the dysfunction, executives may swoop in and shut down a project that has been months in progress, leading to wasted time and further team disillusionment.

- Or even worse, you may launch a product that’s never properly marketed, sold, or supported.

The solution: alignment through shared evidence

There’s only one way I’ve found to overcome these disastrous outcomes: continuously aligning product and business teams around an evidence-based, shared understanding of the customer. This is too often overlooked when we discuss product best practices: people – their egos, emotions, and organizational politics– are actually at the core of product creation. If the people on the extended team are not aligned, the product cannot succeed.

In my previous article, A Product Practitioner’s Playbook for Building Successful Products, I shared my tried-and-true customer validation strategies for each stage of the product life cycle. But it’s not enough for you as a product manager to achieve that understanding. For all the reasons described above, your learnings will be wasted if you don’t bring the rest of the team along on that journey. You must build customer understanding in partnership with the product core team and business stakeholders.

Below I’ll cover two topics:

- How I involve my core team in my customer validation efforts.

- How I identify business stakeholders and share what we’ve learned from customer validation, through multiple channels, over the product life cycle.

All of this builds successful products and happy teams.

How to involve the core team

I’m amazed at how many core teams I’ve encountered where the members aren’t clear on the customer problem a feature or product solves. It’s hard for engineers and designers to create a product if they don’t understand the target customer and their problem. When I was conducting interviews at the Fortune 500 company I mentioned earlier, one engineer said something that was repeatedly echoed across my other interviews with engineers: “We’ve missed out on understanding the fundamental problem…we don’t have the knowledge of the user’s problem to really build the [right] solution.”

Even worse, if team members each have different ideas about the target customer and problem, it’s a recipe for disaster. These teams work at cross-purposes, argue, and become demotivated and disconnected. This is why, from the start of a project, I involve every member of the core team in understanding and validating customer problems. In my earlier article, I took you through the validation techniques I use at each stage of the product development life cycle. Here’s how I involve my core team in each of those steps.

Key documents to collaborate & build a shared understanding

I create a set of artifacts where we document and collaborate on our research approach, review findings, and build our shared understanding of the customer to design the best, lightest-weight solution. The artifacts include documents, videos, and presentations, plus team comments on all of them. I’ll describe them in more detail below. In addition to aligning the team, these documents are a historical record of what questions we asked about our customers, what we learned, and what we decided to build as a result. When a new member joins the team, I share the folder that contains all this information and walk them through this history.

Here are the most important artifacts I create to document the core team’s shared knowledge:

- Research guide & questionnaire: We brainstorm customer hypotheses and research questions as a team. The team also reviews the research questionnaire that the researcher and I write based on those hypotheses.

- The research guide is typically a Google Doc that contains the high-level research questions we’re trying to understand about our customers, a description of who we’re trying to recruit for interviews and how many, our timeline, and a link to the research questionnaire we’ll use in interviews (below). This aligns everyone around the key research questions and methodology.

- The questionnaire: I create a template in Google Sheets, where all the questions we’ll ask during interviews are written down the left column (each question in its own cell) and notes can be taken in the cells to the right to summarize responses to each question. This Sheet is also useful for keeping interviews consistent– asking the same questions of different research participants. Multiple core team members can volunteer to interview or note-take.

- Research session videos/transcripts

- We record all our customer interviews so that we can rewatch them to summarize findings across interviews and so that anyone on the team can review them. It’s always so powerful to hear directly from customers– listen to the language they use, and the frustration or joy they feel about a problem area.

- Findings deck: My researcher and I will then summarize findings and we will review them as a core team. I like to put research findings in a deck because it forces me to be pithy and creates an easily consumable, attractive package.

- Mapping customer findings to solutions: in the last few slides of my findings deck, I include a table where we list each of the customer problems we’ve identified. In the table I create an adjacent column to begin brainstorming solutions, as a core team. I also create an effort vs impact matrix. Both of these are discussed in my earlier article.

I will reuse all of these artifacts to communicate with my business stakeholders and the broader company, as needed. I’ll talk more about this later.

“Shouldn’t engineers be coding – should they really be doing customer interviews?”

I invariably get asked a version of this question when I share my approach of including the whole core team in the customer validation process. This is a flawed question, for a few reasons. The idea that engineers should only code seems reductive. The process of engineering requires collaboration, discussion, and alignment. More importantly, it requires a deep understanding of the customer. Not including engineers in customer validation sacrifices that understanding. And the team collectively will have important perspectives that I alone may miss. The team also needs to be bought into what we’re learning about customers and the problems we’re trying to solve. People who participate are more likely to buy in.

I acknowledge that not every member on the core team will want to engage in research in the same way or have the time to engage. That’s why I always offer opportunities for hands-on work– commenting on research questions, interviewing, and notetaking. But I also offer summaries of what has happened that are discussed real-time (walkthroughs and brainstorms in meetings) and asynchronously (via Slack or email). The information is shared in multiple formats and communication channels. I want to meet each team member where they are. Skipping this communication and engagement leads later to disenchantment and time wasted arguing about our direction.

Share customer learnings with your business stakeholders, early & often

While I’m undertaking customer validation with my core team, I’m simultaneously beginning to identify and communicate with business stakeholders who will be essential to the success of my product. I ask a few key questions to identify my stakeholders:

- Who will be on the frontlines of bringing this product to market e.g. marketing, selling, and supporting this product?

- Who will help make what we’re doing successful?

- Who can block what we’re doing and make it unsuccessful?

I get my core team and manager’s advice to help answer these questions. I also ask stakeholders to identify each other. It can feel like a lot of people to communicate with, but again it’s better to make that the upfront investment so I can better control the conversations and get ahead of people’s concerns.

Executive sponsors

There’s one group of people I haven’t yet discussed– the cross-functional leaders/managers of my core team members. They’re actually the first line of people who need to be bought into what we’re doing (e.g. if the design manager starts objecting to what my designer is doing, the project quickly grinds to a halt). Also, any disconnect between the product and business teams will likely be escalated to these leaders. I call this group my “executive sponsors.”

For my executive sponsors, I like to schedule a bi-weekly or monthly check in. Bringing them along on this journey is essential and more frequent updates share progress rapidly and catch any objections early. The meetings should be small and there should be lots of time for questions.

Marketing, sales, & support leaders + frontline influencers

I identify the marketing, sales, and support leaders who will need to activate their teams to bring the product to market. I will also ask leaders to identify “frontline influencers”– those directly selling and supporting the product who are influential with their frontline peers. Why? I’ve found with sales people, especially, there can be a disconnect between what sales leaders think it takes to sell a product and what their frontline people think/need. Also it’s one thing to hear your boss tell you to sell a product, it’s another to see a superstar colleague increase her deal sizes by selling that product. These marketing, sales, and support teams also have a great deal of insight into customers’ needs and buying habits. I share what we’re learning with them to get their perspective early and incorporate that perspective back into our approach.

Because they’re busy with customer-facing activities, I try to find time with these leaders and influencers during their regularly scheduled group meetings or one-on-one. I always take notes on people’s feedback from these meetings and share them with attendees after the meeting (including any action items) and share the slides. Again, this shares/repeats information across channels and formats.

Company-wide sharing

Depending on the scope of the project, I may also need to think about how to communicate broadly with the entire company. I might schedule “Lunch & Learns” – very open forums where folks can come learn what we’re doing, over lunch. They’re casual and opt-in, but they’re open to the whole company. I can share information and capture any pockets of feedback I may have initially missed. I like to record these sessions and share the recordings broadly.

Get alignment with each group

I get sequential alignment within each group and then move onto the next one; in that way I bring the buy-in of the previous group to the next group. This keeps the process very efficient.

A phased approach: First share the customer-problem learnings, then share the solution

As mentioned with my core team, I always discuss/brainstorm the solution last, after we’ve aligned on the customer and the problem. This centers us on the customer/problem not on the solution. Too often teams jump to solutioning without an understanding of the customer.

This is also what I do when sharing with business stakeholders. I first share the research approach and our customer-problem learnings; I want to first ensure we’re all aligned on that. And then I share the solution/designs and remind stakeholders of how the solution maps back to what we’ve learned about the customer. If you jump directly to sharing a solution, it’s hard to understand whether stakeholder feedback is around your understanding of the target customer problem or around the solution design itself.

As I share what we’ve learned, I ask how it resonates with business stakeholders’ experiences with customers. In this way I’m asking them to ground their feedback in their actual customer experiences, not their egos or opinions. This helps me get their buy-in to our approach and refine my understanding of customer needs.

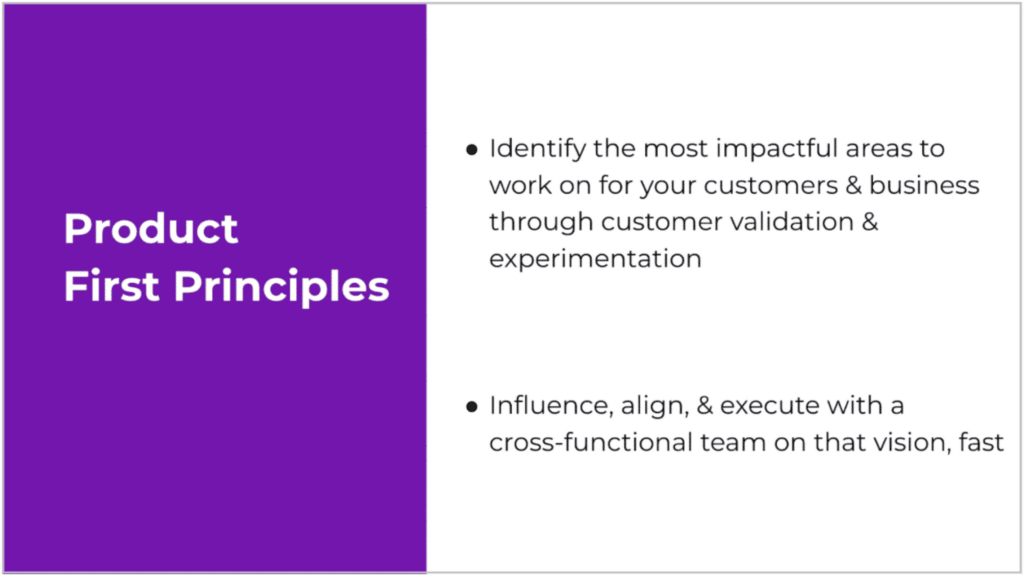

Seek alignment and buy-in, not permission

By grounding my product approach in customer evidence, I’m aligning stakeholders around my evidence-based vision and incorporating their feedback, but I’m not asking for stakeholder permission. This is an important distinction. At the end of the day, it’s my job (and no one else’s) to influence and lead the organization through identifying the most impactful product areas for our customers and business. If I’ve taken a robust and collaborative, evidence-based approach to doing that, I have done my job well. As I discussed in my other article, all of this gets to the heart of our core function as product leaders.

Key takeaways: Customer validation is a team sport

Shared understanding of the customer is the glue that holds a product project together. I use an evidence-based approach to build that shared understanding across my core team and business stakeholders, because I want to avoid egos, emotions, and politics as much as possible. I use the customer evidence to energize and motivate the team– it becomes a banner around which we all rally.

- I collaborate with and involve my whole core team directly in developing, executing and learning from customer validation.

- With business stakeholders, I share our findings about the customer problem first, then our solution/designs. I ask how what we’ve learned resonates with their experience. I’m not asking for permission, but I am getting them bought-into my vision.

- I keep us grounded in a customer evidence-based approach.

- I get alignment within each group and then radiate information outwards.

- I’m repeating information across channels and formats to meet people where they are.

Ask me questions

As always, I’d love to hear from you! Feel free to add your comments, questions, and experiences below or reach out to me directly. Because I believe in the power of user feedback, I’ll continue to iterate on this article’s content based on what you share.

Photo by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of UserTesting or its affiliates.