Contents

- Three key customer questions

- Discovery: Who is my customer? What is their problem?

- Design & build: What is the best, lightest solution?

- Launch and iterate: usability testing and product metrics

- Why this matters: product first principles

- Key takeaways: How to stop building products people don’t use or buy

- Ask me questions and stay tuned for more!

Editor’s note: This is the first of two articles on building successful products, written by Tanya Koshy, a product management VP and consultant. In this article, part 1, she covers how to use customer insight in the development process. In part 2, she describes how to align teams and stakeholders using customer information.

The problem: Too often, we build products people don’t use or buy

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: A decade ago, I joined a startup just after the initial launch of their product. 20+ engineers (yes, they were well-funded) had spent the prior nine months in an office park, locked away from the world. They were building a consumer product that the CEO was adamant would be revolutionary. In anticipation of how massively successful the product would be, the CEO hired 90+ people. The product launched, weeks passed, and…crickets. There were more employees than users.

Over the preceding year, convinced that the product would be wildly successful, the team had neglected to actually talk to any potential users. If you haven’t gathered data and insights to understand your users’ needs, you can’t build a product that meets those needs. And if your product doesn’t meet any users’ needs, you don’t have a business. The year to follow was filled with frenzied ideating, pivoting, and rebuilding. And despite my very best efforts, little that changed in the product was based on any real understanding of potential users. Within another four months, the team and product were shut down.

That wasn’t the first or last time I saw this happen. Time and again, I’ve seen product teams invest huge amounts of time building and rebuilding products without any real understanding of customer/user needs. The result: products people don’t use or won’t buy.

But the ordeal of that startup experience– the finger-pointing, desperately trying random ideas, the extreme uncertainty– set me doggedly on a path to build products and teams differently.

The solution: Continuously validate and invalidate customer needs across the product life cycle

There’s only one thing that I’ve found works in building successful products: systematically learning about and validating your customers’ needs and your subsequent ideas/designs/solutions at every stage of the product life cycle. I’ve fine-tuned my approach over my career leading product and growth teams at places like Google, Facebook, Groupon, and UserTesting, and with my consulting clients today. I want to share my core strategies with you – this is my playbook.

For each stage of the product life cycle, I will discuss the questions I try to answer about my customer and I will share the particular customer validation strategies I use.

Before we dive in, a few terminology notes:

- At times, I use “users” to refer to people who may use my product, and “customers” to refer to people who buy it. My product may simultaneously have multiple user/customer segments, and these folks may be internal or external to my organization. Over my career I’ve built B2B and B2C products for both internal and external users. I’ve iterated upon and applied this playbook in all of these contexts.

- I use “customer validation” to describe the process of testing my assumptions and hypotheses and learning about my customer problem, target market, and product solution. Some people think “validate” means a self-serving effort to prove your hypothesis is correct, but that’s not what I do. Every time, I am equally willing to validate or invalidate my hypotheses or uncover something wholly new. I use “customer validation” to broadly cover all these cases. I also sometimes interchange “research,” “validation,” and “experimentation.” I do so to describe a range of strategies that are focused on being efficient, purposeful, data-driven, and unbiased while freeing myself from the baggage each term sometimes carries e.g. “research” feels pedantic and time-consuming, “validation” feels self-confirming, “experimentation” feels overly quant-y and indecisive.

People often think of customer validation as something you do once you have designs or once you’ve built a prototype. However, it’s important to start validation as early as possible and to then continue to refine your understanding of your customer, their needs, and the market opportunity throughout the whole development process. It saves a lot of time wasted designing and building something customers don’t need. I refine my understanding of my customer-problem-solution over time, but I’m never done – the market and customers change constantly.

Below are the product development stages I’ll cover. Your organization may name these differently or consolidate steps. That’s ok, I think you’ll still find these familiar and applicable.

Contents

- Three key customer questions

- Discovery: Who is my customer? What is their problem?

- Design and build: What is the best, lightest solution?

- Launch and iterate: Usability testing and product metrics

- Why this matters: product first principles

- Key takeaways: How to stop building products people don’t use or buy

- Ask me questions and stay tuned for more!

Three key customer questions

At a high-level, there are three fundamental customer questions I seek to answer across the product life cycle:

- Who is my customer?

- What is their problem?

- What is the best, lightest solution I can build?

These questions are how I focus my team on building successful products, ones that are “valuable, usable, feasible, and viable products,” categories described in-depth by Marty Cagan.

Discovery: Who is my customer? What is their problem?

When I set out to build a new product or feature, I already have some hypotheses about customer needs in a problem space, but I’m really looking for unknown unknowns. Therein lies the revelatory power of user interviews and qualitative user research, in general.

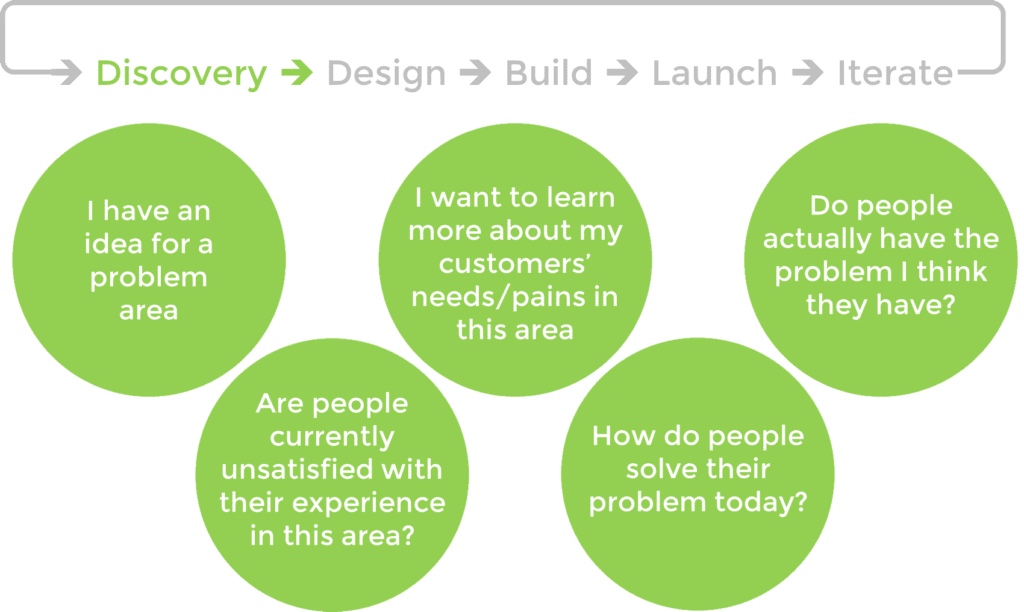

During discovery, this is what I’m focused on learning and validating:

With this in mind, I’ll do 5-8, one-on-one discovery interviews with people who represent my (hypothesized) target customer. I like to spend at least 45-60 mins with each participant.

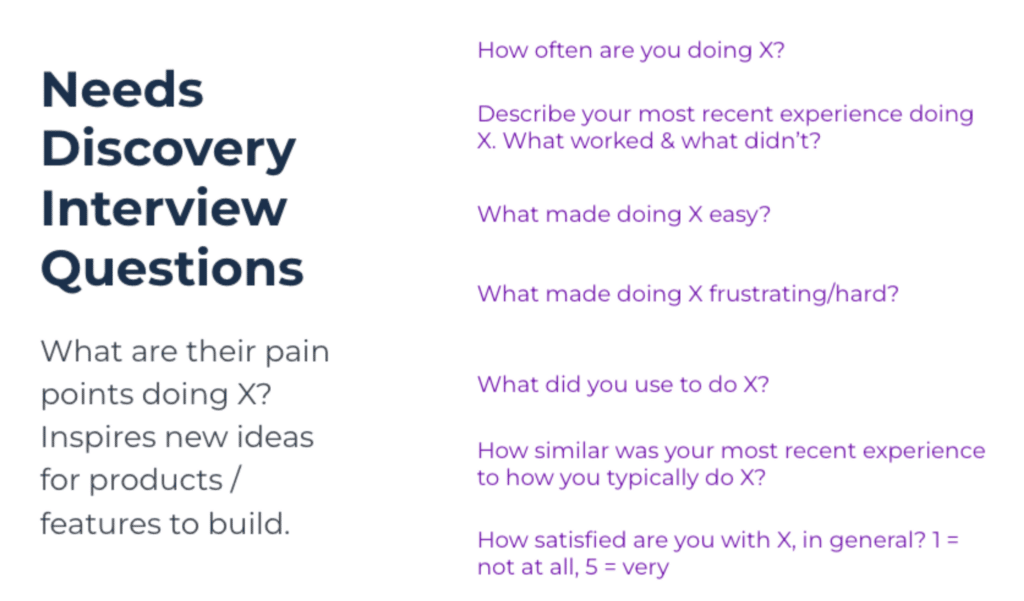

My favorite discovery interview questions

In discovery interviews, I use the questions below. I listen for areas of significant pain with few easy/cheap remedies. I use these questions specifically to keep my participants grounded in their actual behavior, as opposed to hypothetical behavior. That’s essential to accurately understanding and evaluating their experiences.

My questions are open-ended and I keep an open mind. And I ask lots of follow-up questions to dig deeper into participants’ answers.

A note about sample size

I start with five interview participants and expand to eight if I’m not finding themes/patterns in participants’ responses. If three or more people say the same thing, then I am confident that I’ve identified a significant theme: one that will hold, even if I interview more participants. If I have several distinct customer segments, I’ll interview 3-4 people per segment. I often get asked: “Is five interviews really enough?! 3-4 per segment?!” In discovery, I look for significant problems with a high chance of occurrence; these are the valuable problems I want to build products around. The sample sizes I’ve discussed enable me to identify these types of problems. Jakob Nielsen wrote a great article on the topic. Yes, Nielsen’s article is about usability testing in particular, but my numbers and discovery approach have also been informed by and validated by the countless, well-trained UX researchers I’ve worked with.

Coming out of discovery, I have a better understanding of my potential customers’ experience and needs.

Case study: navigating fraught emotions and discovering early pandemic trends

We often write so dryly about research and customer validation, focused on the methodology and tactics. It’s easy to gloss over how emotionally fraught and organizationally sensitive uncovering findings about customers’ needs can be. In this detailed case study, I want to share:

- Specific examples of the discovery strategies I described earlier

- How people’s emotions can flare up around interviews and findings and how to handle that with empathy

In the middle of 2020, I started consulting for the technology arm of a large, global commercial real estate firm. The team wanted to build the next generation of their global office leasing product and wanted advice on their product strategy. As I most often do, I recommended that we start with a round of discovery interviews to understand customers’ needs in the space. It was still relatively early in the global pandemic; lockdowns had started in the US around March 2020. And while it was clear that work-from-home had immediately cleared out office buildings across the world, the full (and long-term) impact of the pandemic on the commercial real estate office leasing market was unknown. It wasn’t even clear that there would be a long-term impact. We all still thought the pandemic would be over in a few months and that things would go back to business as usual.

Discovering unknown unknowns

So when I suggested that we do discovery interviews, I thought we’d learn about the office leasing market as it had been and where it would return to shortly. I figured we’d find themes in customer feedback that would help us prioritize and focus our product strategy. After all, this was a mature market that the company had been in for a very long time. I had no idea that I would stumble upon early warning signs and far-reaching market trends that would shake up the office leasing market for years to come.

My research partner and I planned to interview commercial brokers and their customers who were leasing office space around the world. On our first day of interviews, we talked to several brokers in the US. We used many of the discovery interview questions described earlier, and also added a set of introductory questions I use when interviewing users of B2B products. We asked:

- Tell me about your role

- What are your business goals for the year?

- What keeps you up at night?

- How many office leasing deals did you do this year?

- Walk me through your most recent one

- What was hard?

- What was easy?

- What would you change?

- What tools did you use?

- How satisfied are you with the experience?

- How similar was this most recent experience to your typical experiences?

On that first day, we immediately learned that brokers were beginning to see an influx of customer requests to vacate existing leases, sublet, renegotiate leases, and almost no one was looking to lease new office space. Commercial real estate has long sales cycles, so brokers work their sales pipeline for a long time to close deals (ideally multi-year lease agreements), and it’s a sales commission based job (deals = salary). The brokers were really stressed out as their deal pipelines dried up and the future remained uncertain. Something significant was happening, and these brokers were on the front lines living it.

Sometimes there are internal hurdles to contacting customers, so recruit people externally who are like your target customer

We kicked our research into high gear, aggressively recruiting brokers and customers to talk to. It wasn’t easy. Brokers were understandably protective of their client relationships, more so now than ever. So when it became tough to find existing customers to interview, we recruited externally. We targeted executives who had recently done a commercial real estate transaction for their organization (i.e. people like the target customer, though not a current customer).

Be compassionate

And across our interviews, we trod carefully – this was a really hard time for everyone. We were talking to commercial real estate brokers who were watching their deals dry up while also servicing clients wanting to renegotiate leases. Harried executives were trying to figure out remote work and what to do with the existing, empty office space they were still paying for.

Everyone was doing all of this while dealing with the pandemic’s impact on their health and families. As interviewers, we were flexible, kind, and grateful. I did a lot of extremely early and late calls to accommodate global time zones and participants’ work and family schedules. I sent a lot of thank-yous and follow ups.

But it was also a time when talking to someone sympathetic and genuinely interested (me) broke up the strange tedium that crises can create. I’m sure you can relate: working, Clorox-wiping your groceries, in your pjs at 11am while trying to manage your kids’ online school sessions, all with no end in sight, you probably would have liked someone to ask you about your needs. And honestly, listening to someone else’s troubles helped me feel less isolated too.

Truly distinct customer segments = more interviews

The customer segments were multidimensional and distinct: brokers’ needs were different from customers’, and varied around the world and across all business types and sizes. All of this intersected with the unusual nature of the pandemic. As a result, we did a lot of interviews to account for this complexity (50+, but only 3-4 participants in each segment). We wanted to be quite certain about the patterns we were seeing, across very different markets and customer segments, hence our willingness to interview more participants. But because we were also seeing such significant, resounding patterns in our interviews, we sped up our research timeline in order to share our findings as quickly as possible with the team.

Hard truths

We finished 50+ interviews and summarized findings in about 45 days. It was exhausting, but essential to move quickly. Here were some of our findings:

- Executives were grappling with remote work and how to get their employees to ever come back into the office;

- Executives wanted help reconfiguring office space to accommodate changing Covid protocols and remote work;

- Executives wanted more flexible lease terms and more flexible office space to account for fluctuations in how many people were using an office; there was a significant chunk of employees who wanted to stay permanently remote.

We were confident in our approach but still nervous to share our findings. It was early in the pandemic, and yes there were other confirming indicators, but around the world there was also hopeful/wishful thinking that things would resolve quickly and go back to normal. However, given the significance of our findings, we knew we had to be bold, truthful, and push for a sense of urgency. The patterns were so clear as we talked to our participants that we knew this could have a big business impact. We said: “These are the resounding themes we’ve heard across participants, regions, and business sizes. We think they’ll have an impact on your market and product strategy moving forward. And now, in partnership with you, we’re going to develop product strategy recommendations to act decisively.”

A note about sample size and stakeholder pushback/emotions

The team was impressed by the scope and speed of the work, and the findings conveyed the gravity of the situation. But we also got a few questions about sample size and methodology, despite having shared the proposed research approach before ever starting any of the research. “Is this enough people to interview– it’s a global business? It’s only been a few months.” I explained the methodology and why it was sound, and I discussed how resounding the themes were across a diverse and representative group of participants. I also pointed out that these were trends in the business they were already seeing; the pandemic was just an accelerant.

I want to highlight that when I get these questions about sample size and methodology (which I often do), it’s not because my audience truly cares about sample size and methodology. I usually share my research approach before ever starting the research; funnily enough, I most often get questions about methodology only after I share findings. Maybe some folks care about methodology, but most people ask this question because I’ve shared something new that is uncomfortable, hard, or scary. These are emotionally fraught discussions – having to rethink our approach, leaving behind ideas or projects we’re invested in. So instead of getting to work and changing what we’re doing (which is hard), we argue about sample size and methodology. Please don’t make that mistake. In this case, the team got to work.

Hard truths will set you free

In the months to come, as we worked with the team on a product strategy to address these changes, the themes we’d identified early (our tiny two person team, doing one-on-one interviews, in a month) were independently and repeatedly confirmed in the press and by external market research firms.

Two years later, we’re all still grappling with the changes to how and where we work. It was a good reminder, even for me (a believer), on why doing these types of discovery interviews with customers is essential. The needs our research identified were big. I’m not going to pretend like the product team solved them overnight, but they started work early based on our findings – they were ahead of the game. The product team also used the relationships we’d built with the brokers and customers we’d interviewed to subsequently recruit participants for early alpha and beta tests of their new product (bonus points)!

Design & build: What is the best, lightest solution?

Coming out of the discovery phase, I have better identified the target customer and their problem/needs. My core team and I start brainstorming solution ideas to address those needs.

Brainstorm solutions that map to customer needs

To facilitate the brainstorming process, I’ll create the table below. One column lists all the needs we’ve uncovered through our discovery interviews. The second column is for inputting our solution ideas during our brainstorm session. Why? It’s often easy when brainstorming product solutions to get distracted by shiny features that don’t actually solve a customer’s problem. Using a table like this forces the team to align every solution to a customer need.

<Target Customer Description>

| List the needs in this column | List the brainstormed solutions here |

| X | A, B, C |

| Y | D, E, F |

| Z | G, H, I |

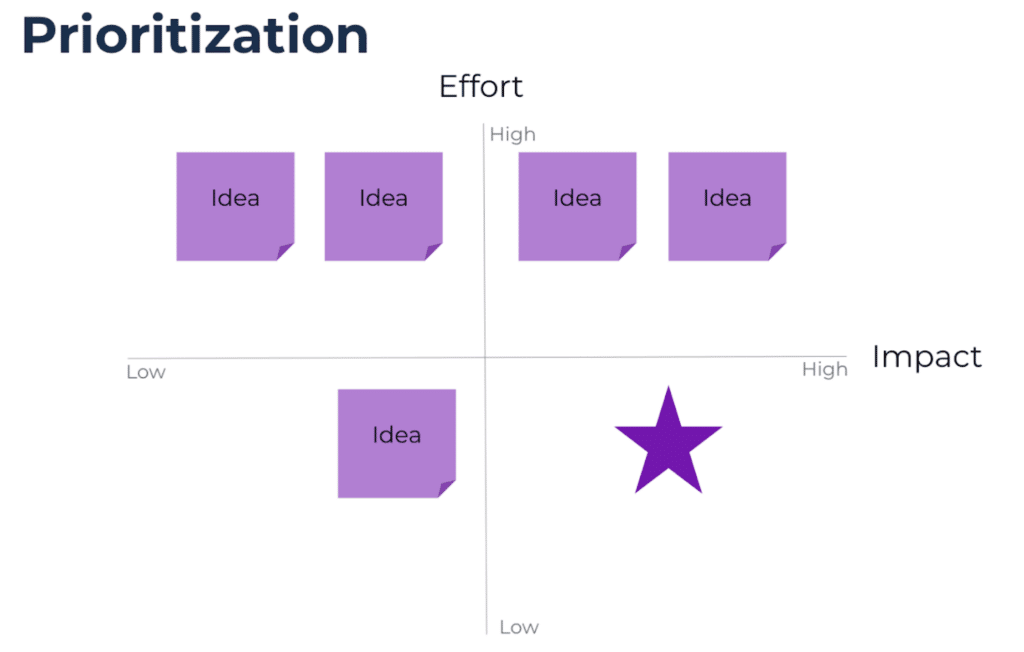

Effort vs impact matrix

But we can’t build all these solutions; I want “the best and lightest solution.” Time is a limited resource when building and shipping products. We always learn more about our customers’ needs and behaviors when the product goes out into the world, so we’ll inevitably have to iterate upon it. I want to avoid overbuilding wherever possible.

In this next step, as a core team, we take all the solution ideas we’ve mapped to customer needs in the table above and we drop the possible ideas onto this matrix below.

We use high, medium, and low to estimate build times and similarly to estimate the customer impact (how well does this solution meet the customer need, how valuable/significant is that need?) We’re looking for high impact, low effort solutions.

Case study: avoid overbuilding

I worked on a project where we were designing the very first scheduling system for the drivers of a same-day delivery service. It was a complex problem because we worked with many transportation companies, all with different external scheduling systems for their drivers. We also had to integrate with several internal systems. We had to predict customer demand for delivery, schedule drivers accordingly, dynamically adjust the schedule if volume spiked, assign and monitor routes for drivers on a shift, and comply with scheduling/labor laws. We were a small development team: I was the Product Manager, and there were three engineers. It would have taken forever to build all that functionality.

After a prioritization exercise similar to the one above, we decided to focus our energy on quickly standing up a scheduling system that predicted demand and sent out a request for the necessary drivers directly to the transportation companies. Rather than building elaborate front-ends that integrated with the existing scheduling systems, we used Google Sheets to dump in the requested number of drivers. The transportation companies had people who manually created the schedules in Google Sheets, and we read that data to assign routes to drivers during shifts. This wouldn’t be the end product, but this early prototype helped us refine our understanding of users’ needs and uncover new ones, refine our prediction models, and iterate upon the product.

Even after the effort vs impact exercise, the team may be considering several solutions. I want to save design time. For each solution, I think of the value proposition & high-level feature set that best represents the solution.

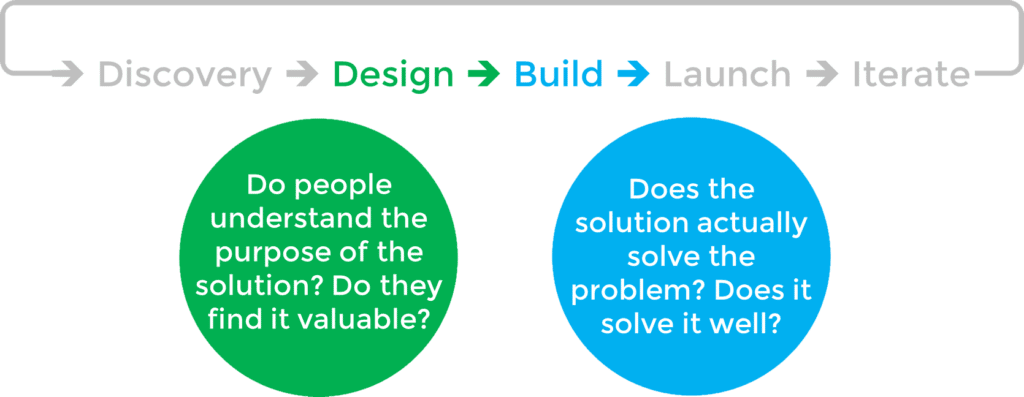

Before getting into the details of what the solution will look like in wireframes or mockups, I validate my value proposition and feature set. This will help us better target our designs. These are the key questions I want to answer:

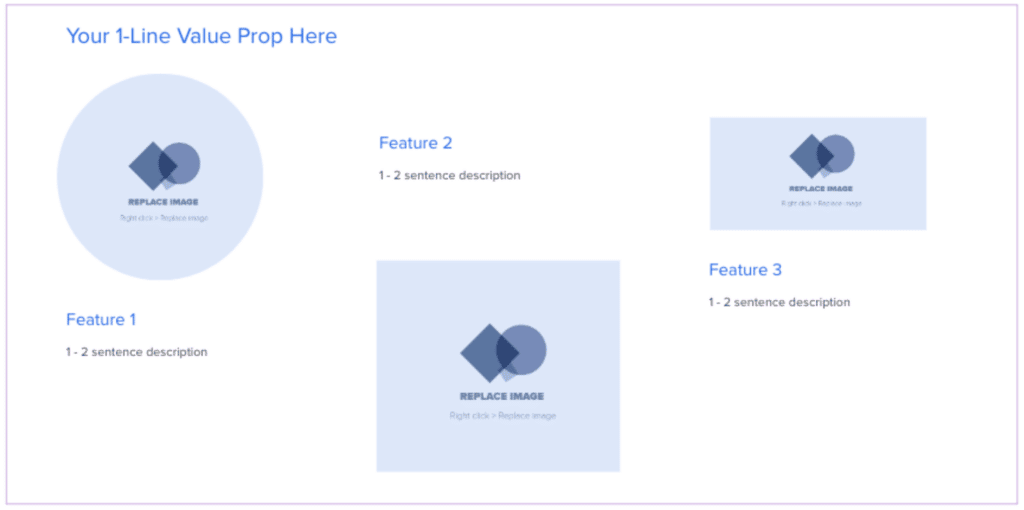

Landing page template & interview questions to test value propositions and feature sets

I take my value propositions and feature set ideas and put together landing pages that describe them. Here’s a simple landing page template I’ve used.

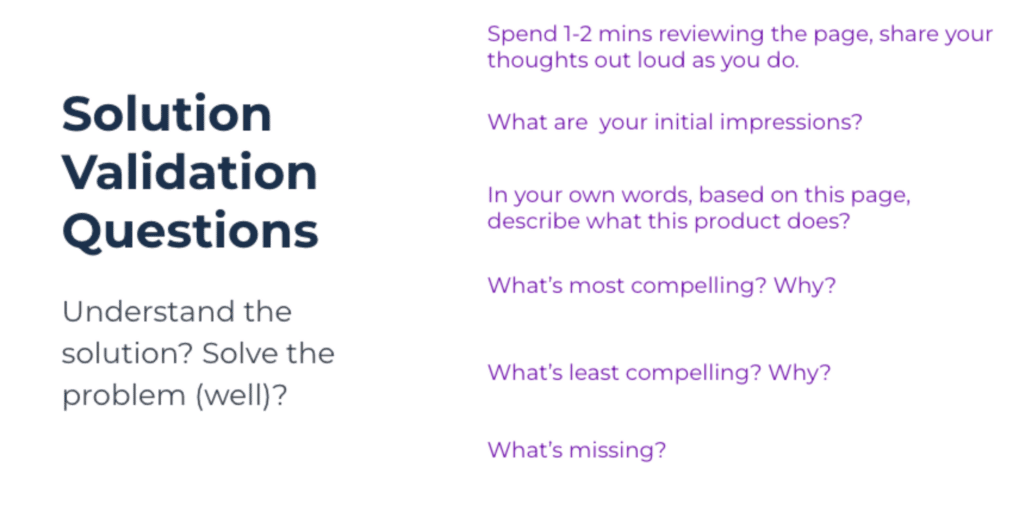

I’ll do a round of 5-8 one-on-one customer interviews, with new participants, to look at the landing page. I want to know if they understand the solution and value proposition and whether they find it compelling. Here are the types of questions I ask:

I’m always looking for themes in responses across participants to guide my decision-making. This helps me avoid cherry-picking only those responses that validate assumptions I have. I use participants’ responses about what’s most and least compelling to prioritize the features we’ll design.

I also often use the specific words from people’s responses to rewrite my value proposition – I want to speak to my users in their language. That reworded value proposition can go into our UX copy and marketing materials. With a refined understanding of our value proposition and feature set, we can now produce targeted, high-fidelity designs, and build the product.

Launch and iterate: usability testing and product metrics

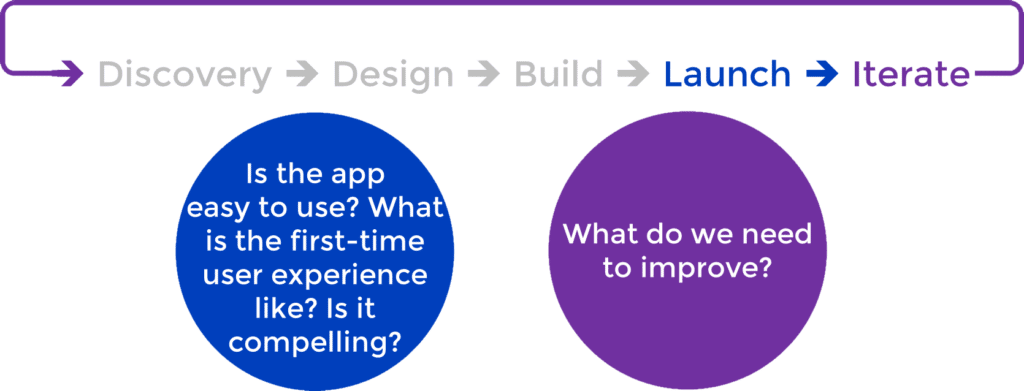

With designs or early prototypes complete, we’re getting closer to launch. During this phase, I’m focused on answering the questions below. So I will do a few rounds of classic usability testing, iterating on the design each time.

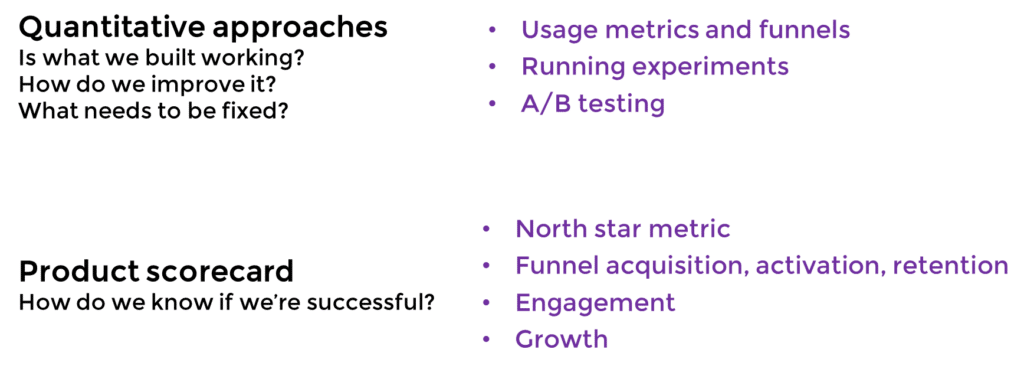

How to set and track product success metrics: north star metric and product scorecard

Once the product launches, I track quantitative measures of customer/user behavior. Prior to launch, as a team, we’ve discussed the key measures of customer value and business value we want to track. How do we know if our customers are happy and deriving value from the product? How do we know if we’re delivering value to our business? We set targets for what we want those numbers to be and/or how we want to move them. We pick one measure to lead the pack, our North Star Metric (NSM) and prioritize our future iterations around improving that metric.

Check out Sean Ellis’s awesome posts on choosing your NSM (here and here). This is how we gauge the success of our product and prioritize our future efforts. We implement web analytics to track in-product behavior and implement tracking for our sales funnel, as well (if that’s handled by an Enterprise sales team, it may not be tracked fully in-product).

I’ve found it helpful to create a product scorecard that tracks these metrics. This can be a dashboard or even a slide that we update periodically, but it’s a simple way to see all our metrics in one place. We review the scorecard periodically as a team. As we uncover changes in the metrics, we may do additional rounds of user interviews to dig into the “why” behind these changes. We might also use an experimentation or A/B testing platform to run experiments to see if we can address these changes and improve our metrics.

And then when we have an idea for a significant new product line or feature, we kick off the discovery process again.

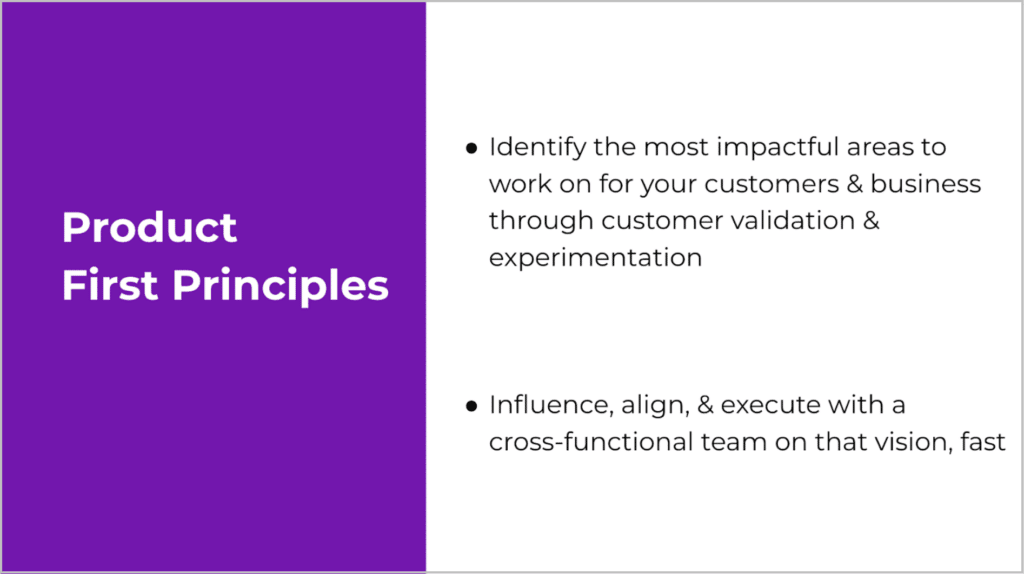

Why this matters: product first principles

I want to return to why all of this matters. I believe it cuts to our core purpose as product people.

Everything I’ve covered in this article is about the particular strategies I use, at each stage of the product life cycle, to do that first piece: customer validation and experimentation. In a subsequent article, I will tackle how to influence and align your organization around what you learn and your product vision.

Key takeaways: How to stop building products people don’t use or buy

1. Focus your customer validation efforts, across the product life cycle, on answering:

- Who is your customer?

- What is their problem?

- What is the best, lightest solution?

It’s never too early to begin this process!

2. Use one-on-one discovery interviews to identify areas of significant customer pain/need, where there are no easy substitutes. Refine your definition of the target customer.

- Account for people’s emotions– interview with compassion and share findings with empathy, confidence, and integrity.

3. Focus your team’s brainstorm sessions on only solution ideas that map directly to identified customer needs. To save design and build time, prioritize those ideas based on effort vs. impact.

4. Don’t jump immediately to creating wireframes or mockups. Translate solution ideas into value propositions and feature sets. Use landing page tests to further validate. This will help you better target your designs.

5. Now, translate validated value propositions and feature sets into designs. Do usability testing to validate and iterate upon your designs or prototypes before launch.

6. Use a North Star Metric and product scorecard to establish and track success metrics after launch. As you identify new opportunities or questions, (re)start discovery interviews.

Ask me questions and stay tuned for more!

I’d love to hear from you! Feel free to add your comments, questions, and experiences below or reach out to me directly. Because I believe in the power of user feedback, I’ll continue to iterate on this article’s content based on what you share.

In my next article, I will discuss my framework and strategies for getting buy-in for customer learnings across an organization:

- How I build alignment with my cross-functional core team (Product Management, Engineering, Design, Research, Product Marketing), in collaboration with my stakeholders (Executives, Sales & Support, and more). I build a shared understanding of the customer in order to accelerate product development, sales, and support. We also collaborate on the setting and tracking of product metrics.

- I’ll also cover the types of organizational resistance you might encounter, how to combat them, and ways to timebox your activities to accelerate your team’s decision-making.

All of this builds successful products and happy teams. Without that organizational collaboration and alignment, all the strategies above are wasted. Stay tuned!

Photo by Max Leveridge on Unsplash

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of UserTesting or its affiliates.

Contents

- Three key customer questions

- Discovery: Who is my customer? What is their problem?

- Design & build: What is the best, lightest solution?

- Launch and iterate: usability testing and product metrics

- Why this matters: product first principles

- Key takeaways: How to stop building products people don’t use or buy

- Ask me questions and stay tuned for more!