Table of contents

- The path to design

- Good design means embracing ambiguity in business

- How to create change in an organization

- Why innovation labs fail

- Evolving the AAA home page: The benefits of focusing beyond price

- Learn empathy for your internal stakeholders

- Design thinking is really just creative problem solving

- Agile should not be waterfall with sprints

- Democratization means “this is important”

- Foster a culture of learning

- About CXI Labs

James Lane is a customer experience strategist and thought leader who also gets his hands dirty with real-world design issues. As senior product design manager at the American Automobile Association (AAA), he drove an award-winning redesign of the company’s home page that dramatically increased conversions and revenue. He’s now principal of CXI Labs, a customer experience (CX) consultancy.

We talked with James about the proper role of customer experience in a company, the backstory of the transformation at AAA, his advice for design and CX practitioners who are trying to drive similar changes in their own orgs, and his career path. Some highlights:

- To show senior executives the value of great CX, you have to empathize with their needs and explain it in terms that they value. It’s not about teaching them why great design is wonderful, it’s about showing them how it solves the problems they care about.

- To implement a big CX change at a legacy company, you have to be patient, find an executive supporter, and learn to speak the language of quant. James used his own experience at AAA as an example, sharing the details on how the change happened despite many entrenched assumptions and processes.

- The goal of “democratization” is not to democratize research, it’s to democratize the sort of thinking that leads to great customer experiences. Scaling research is just one part of that effort.

- Empowering other people to do research will likely increase researcher jobs, not decrease them, just as democratizing data science increased demand for data scientists.

The path to design

Q. Tell me about your background. How did you get into design?

I was in high school as the ‘90s dot-com boom was heating up, and like a lot of kids at the time, I was obsessed with computers and started teaching myself web design. That led to an after-school job with a local ad agency where I would convert their print work into websites, which gave me an early grounding in marketing, branding, and design.

When it was time for college, I did a year of computer science but decided I was more interested in visual and functional puzzles, so I left and went to The School of Visual Arts in New York. Of course, at the time, that wasn’t an easy conversation to have with my parents. Young millionaires were being minted daily, but when the tech bubble popped, art school was a less controversial path.

After my sophomore year, I got a summer job with McCann Erickson that stretched into a couple of years. I ended up overseeing design and production for the US Airways frequent flyer portfolio, along with work for brands like Buick and Xbox. I’d occasionally miss class to go on press checks, but my professors didn’t mind as long as I came back with samples and stories to share with the other students.

Once graduation came, I was looking for a bigger challenge on a smaller scale. I joined a boutique marketing firm, managing campaigns for Virgin Atlantic, Johnnie Walker, and others. That job gave me my first real lesson in the economics of design. For years, creative services had been a value-add for the core business, but that approach had become an issue. After all, when the cost is zero, clients will grow to expect endless revisions. It was a challenging transition, but I was able to convert those operations into a profit center.

From there I went to Showtime, just ahead of some explosive growth. I went from describing Showtime as “You know, not HBO…,” to people saying, “Oh my god, I love Dexter!” Almost overnight, our marketing collateral volume tripled, but our team stayed the same and we were drowning. Thankfully, I had just enough coding confidence to automate certain key processes, which then led to a series of internal products. I had become what I now know of as an “intrapreneur,” but at the time I was just following an instinct for problem-solving.

The experience led me to ask, “What is this instinct? How can I do more of this work?” I’ve always loved complex puzzles involving people and technology, but I didn’t understand how it could be a job. It was around this time that Design Thinking was building momentum. I was amazed to see how my instincts for problem-solving had been codified for business, which led me to an MBA in Design Strategy program in San Francisco. So I headed west and immediately felt like a fish in water.

Good design means embracing ambiguity in business

The MBA in Design Strategy is a new breed of MBA, focused on managing business ambiguity, which modern markets are filled with. You accept that the business operates in a complex ecosystem, with many unknown unknowns, and you embrace that ambiguity to find novel solutions to business challenges.

I found this contrasts with traditional MBAs, which are rooted in an industrial-era mindset: The operations exist, you’re there to administer that business in a predictable fashion, and change happens over a period of years. This leads to a worldview defined by spreadsheets, where anything that can’t be neatly tallied isn’t valued. Businesses create huge blindspots for themselves, along with a false confidence, by adhering to the dogma of spreadsheets.

Executives say things like, “the numbers don’t lie,” but the numbers don’t tell the whole story either. Another one you hear is, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” which is only half the quote and entirely to the contrary. The actual statement is, “It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it — a costly myth.” But those sorts of sayings persist because they bolster that spreadsheet bias.

Now, a saying I like to offer them in return is from a sociologist who said, “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” Reality isn’t neat and tidy, it’s messy and unpredictable. New challenges can come from any direction, and seismic shifts can seemingly happen overnight.

There’s a lot out there that doesn’t fit neatly into the cells of a spreadsheet but is critical to an organization’s success, or even survival. Qualitative data is just the other side of the data coin, even if it’s harder to wrangle, or subject to interpretation. I think that’s what Design Strategy does well: identify the levers we can pull to drive downstream, quantitative outcomes.

That’s not to say I don’t value quantitative data. I love a good spreadsheet, and behavioral data at scale is often where the story of change begins. My concern is for the overweight position the vast majority of businesses hold when it comes to quant versus qual.

Ideally, you move back and forth between these perspectives: uncover trends, explore what they mean, then validate your solutions. But what’s typical, once trends are identified in hard data, is that a company will make what amounts to a leap of faith, often based on the presumed expertise of leadership, who then interpret results through that same lens. What their data never shows is the full cost of their choices, so even what looks like success could be a small piece of a larger opportunity.

There are a lot of assumptions baked into that top-down, inside-out process because the spreadsheets provide a sense of certainty. Organizations are just people after all, and people have a hard time with ambiguity, especially when their livelihoods are on the line. My mission is to show how design can enhance outcomes and confidence by embracing ambiguity.

How to create change in an organization

Q. Say somebody is reading this and they think to themselves, “That’s it. That’s the sort of awareness I want to drive in my company.” Any suggestions for them on how to pursue that? Where to start, what to watch out for?

A. Forgive the typical consultant answer, but it depends. What is that person’s role? Where do they sit within the organization? How do they impact the customer experience? Change is a function of culture. You have to be realistic about your influence and the design maturity of your organization.

But let’s say you’re an individual contributor trying to create change. You’re passionate about delivering a great customer experience, and you want to do more research, but your organization is resistant. I’m not gonna lie, it’ll be tough, but it’s certainly possible. First, it’s important to set your expectations appropriately and focus on incremental growth, or you’ll just frustrate yourself and others.

From there, I’d recommend finding an executive champion: someone who shares your passion for delivering great customer experiences, but is also plugged into leadership priorities. Accept that the world they inhabit is strictly quant, and arm them with the weapons they need to go to battle for you.

Turn your qual superpowers back onto your internal stakeholders. Empathize with their worldview, which is driven by specific metrics, and give them a message they can understand. And, as you do so, make clear that subtle qualitative insights were the starting point. They’ll then be able to connect the sequence of events to quantitative outcomes.

It’s not enough to say, “We spoke to a few dozen people and the majority of them said X.” Your org’s quant perspective will come back with a large-scale survey from five years ago that shows Y or Z is important. You’ve got to find a way to take those qual insights and test them at scale. That way you can come back and say, “X% of this statistically significant pool of people have confirmed our research, which will drive these important metrics.”

You see it in Marshall McLuhan’s precept that “the medium is the message,” where the medium itself drives perception. Spreadsheets appear authoritative because people see numbers as being inherently unbiased. But the people building those spreadsheets embed their bias by selecting certain metrics and excluding others. They show a lot of “what” and little “why,” which leaders then filter through their own perspectives. So if you’re trying to drive a new way of doing business, understand that you’re really trying to change the way an organization sees the world and itself. That’s where culture comes in.

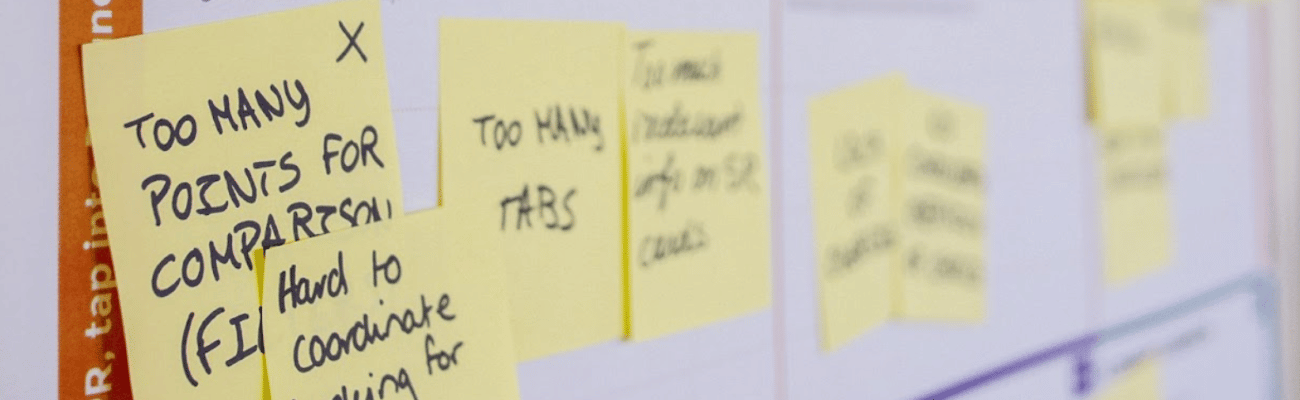

During my time at AAA, the meta challenge I encountered was a culture that was strictly focused on quant measures. Their operational excellence had replaced customer empathy, so the organization struggled to take in qualitative data and value it alongside years of surveys. For example, survey data said that price was the most important attribute, so that was the primary feature on the landing page. When I took screenshots for presentations, the only thing you could see clearly on the home page was the price. So what do you think people focused on?

Roadside assistance is actually an emotionally charged product because it’s a matter of security and safety. Of course, we inherently understood that, but didn’t know how to make use of that understanding. What the qual research found was that when you reduced our offering down to a price comparison, people judged us on a very superficial level.

By deeply engaging with our customers, we found that price was not a top priority, and leadership found that very difficult to accept. A feeling of being cared for didn’t come up in our surveys and certainly doesn’t fit into a spreadsheet. It’s a bit like the “faster horse” quote attributed to Henry Ford, which often gets distorted to dismiss calls for customer insight. It’s really about the need to tease out root issues and not accept answers at face value.

Based on the root issues the research revealed, I developed a prototype that divided consideration into emotional and rational components, placing features and pricing on a second page. It was immediately dismissed by leadership because it was counter to years of large-scale survey data. The approach challenged their worldview to the degree that they wouldn’t even bother to test the prototype. It was dead on arrival.

Why innovation labs fail

Q. How did you wind up at AAA? You had this MBA in Design Strategy, what made you pick the Auto Club as your destination?

A. Coming out of grad school, I was specifically looking for a legacy brand that I felt, from a brand equity perspective, had untapped potential. AAA fit that bill, and largely still does.

At the time, somewhat naively, I thought I could teach a dinosaur to dance and joined an innovation group within the company. Like a lot of large companies at the time, they had a Bay Area-based innovation lab focused on developing technology-driven customer experiences. What I found for myself, and in conversation with people at other innovation outposts, is that these labs don’t work.

It’s what Steve Blank calls “innovation theater.” Executives feel a pressure to innovate, don’t know how to drive that in their existing operations, but are compelled to do something. These labs are opened to great fanfare, as a signal to markets that these legacy brands are about to do something big, but most have been quietly shut down.

The problem is that organizations often don’t know how to handle the insights, ideas, and innovations these labs are intended to produce. They’ve been purposefully placed outside core operations, so their solutions often don’t include many of the operational realities the org contends with. They’re also disconnected from the culture of the org, so alignment can be an issue. Worse still is what these labs say to the rank and file: this is where innovation happens, you just run the engine.

Innovation needs the right environment to thrive, so my company’s name is also the mission. Building on successful design sprints, we work to help clients integrate a customer experience innovation lab point of view into their existing operations. Not in a renovated warehouse far away, and not a farmed-out or stifled half-measure, but home-brewed and driving real results. We love design sprints, but the idea is to pass the baton. When good customer experience design becomes part of the culture, that’s the sustainable edge.

Q. So there you were in an innovation lab, which you said didn’t work. What happened then?

A. Like a lot of innovation labs, we were doing great work that was doomed from the start. We developed a product called Online Garage that helped members manage vehicle maintenance. Not only did our members love it, but it challenged assumptions held by prospects. We’d get feedback like, “Wow! This isn’t what I expected from AAA,” which is exactly what we were going for. AAA has a brand perception issue that this product was able to overcome.

Unfortunately, the organization had a tough time nailing one thing and growing organically from there, so feature creep was an issue from day one. In reality, we were competing against an envelope in your glovebox, or file folder at home, helping to organize your maintenance history, with the addition of reminders. But the only way to gain executive support was to target a robust repair ecosystem at launch.

Our innovation lab was eventually shut down, and I moved into the larger org, joining their digital marketing team, where I heard, “We’re here to run the engine” a lot. Curiosity wasn’t rewarded. We were there to optimize, not evolve.

I had grown tired of producing good work that went nowhere and was job hunting when a restructuring opened possibilities. The company had a new CMO, and I had a new boss, who said, “I trust you to do what you think is right.” A blessing at the time, but not something you can count on for innovation.

Evolving the AAA home page: The benefits of focusing beyond price

So I knocked the dust off my acquisition funnel prototype, which had sat untouched for almost two years, and started to refine the approach. The new design prioritized an emotional connection, greatly reduced content, and clarified our offering.

When it came time for a full A/B test, the response was so overwhelmingly positive there were concerns about data fidelity. Naturally, we made sure everything was working properly and confirmed that the massive 35% lift in conversions we were seeing was real. Better yet, we had more customers choosing higher tiers of membership, driving even more revenue gains.

Despite the great results, it was difficult for the organization to accept. After all, previous optimization attempts saw one or two percent gains. So the test dragged on for months until Labor Day weekend, which is the unofficial start of road trip season and a peak in AAA’s year. The new design was seeing a staggering 85% lift, with the legacy design flat week-over-week, entirely unaffected by the holiday. The opportunity cost was now just too high to ignore, so the test was ended and the new design fully implemented.

To me, it’s indicative of how difficult change can be. Certain corners of the org fought hard to find reasons why this couldn’t possibly be true. After all, they were experts in selling the value of AAA and had years of survey data to prove it. They couldn’t comprehend how talking to a couple dozen people, stripping out most of the content, and pushing pricing to a second page, could have such an effect.

The research showed that our legacy website was perceived as brochureware. The design felt generic, and with every business line fighting for space, the result was an overwhelming experience. It became a reflection of our priorities, not the customer’s. That’s a common problem for legacy companies with a broad product portfolio, the org chart drives design.

To your earlier question about the advice I’d offer to someone in a legacy organization, it’s to start small and focus on steady growth. You can’t change everything at once. The Navy SEALs have a great phrase for this: “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

If you want to create change, you need to move smoothly through the transitions of becoming more agile. With culture, you’re talking about uprooting very ingrained ideas, held by many people, about how things work and where they fit in the marketplace. That’s not something you can do overnight. You really have to bring the whole organization along.

So that’s what we did. Naturally, the homepage redesign got a lot of attention across the org and that gave us the foothold needed to take on the entire website. We built the business case, the strategy, and the team, and got to work. We knew we had to go back to customers, but also needed to understand how each line of business saw the world.

Through a series of workshops and presentations, we crafted our approach and captured their perspective. This ensured our solutions would address real business challenges and move critical metrics. The results were happy customers and big wins across the company, but more importantly, the seed of a sustainable advantage had been planted. This heavily quantitative culture was now able to measure the value of a balanced approach.

Q. You mention people naively believing they could easily drive change. I’ve heard the backlash from that, including people who question whether change is even possible. I hear, “It’s so big, it’s so complicated, it’s so hard. Let me just focus on my task or my little thing, and let me not worry about the rest of it.” Any advice to them? How should they balance out their thinking?

A. You’ve got to have some sort of North Star for what the future looks like. Even if you just have a vague idea of what’s right or wrong about a particular sliver of the overall experience. Use that to gain a foothold, but don’t expect it to be the change.

The acquisition funnel redesign had a crazy, outsized impact. But one of the things that stuck with me is how few people asked why the redesign was successful. More than a few thought I just hit it with the pretty stick, and that a modern look was the answer. They didn’t understand, or even know to ask about, the underlying strategy behind the choices being made. And despite trying to communicate that strategy many times over, I was still speaking a foreign language.

Learn empathy for your internal stakeholders

For a lot of people unfamiliar with qualitative work, it can be challenging to even know what questions exist. They focus on the UI design, because it’s an artifact they can understand. As a UX researcher or designer, or a leader of those teams, your most important role is translator.

Our language is qualitative and theirs is quantitative, so you have to show empathy for internal stakeholders, just as you would for customers.

Q. That one feels key, so let me repeat it back. Many of the researchers and designers I speak with think about the process of creating empathy for the customer (or for the user). And how to spread that empathy across the company.

I think what I’m hearing you say is that you need to apply that same sort of thinking to your internal counterparts or clients or stakeholders, and get inside their heads just as heavily as you try to get inside the heads of the end-user customer. Am I getting that right?

A. Absolutely. Your bosses are stakeholders, interview them. Work to see the world from their point of view. You know you can’t deliver a great product without understanding what that product means to a customer and how it fits into their life. If you’re hitting resistance, consider what this product means to your internal stakeholders. What’s driving their perception of success? If they have specific metrics they’re judged by, the touchy-feely stuff doesn’t matter. Will those metrics move? That’s how they view the world, so lean into that.

Consider what this product means to your internal stakeholders. What’s driving their perception of success? If they have specific metrics they’re judged by, the touchy-feely stuff doesn’t matter. Will those metrics move? That’s how they view the world, so lean into that.

One of the more interesting lessons I’ve encountered, with regard to internal stakeholder perspectives, really came at me sideways. The initial project scope was simple: evaluate and redesign the client’s primary landing page for a subscription product. That page would drive traffic into an existing transaction flow, but it was only near the end of that transaction that visitors learned the price they’ve seen is inclusive of a small fee. Not a large amount, and same total price, so not exactly a bait-and-switch. But as one tester said, “I’m literally typing everything in, why is there a fee?” It was a faint but specific qualitative signal that never appeared in price testing at scale.

We dug in, and of course, it had “always been done this way,” but was driven by the priorities of another group. It turned out the fee existed to realize a slice of that transaction now, because the business amortized those revenues across a year, and it also allowed them to keep a bit more revenue if monthly subs churned out. I could see the logic, but the emotional response of customers was palpable.

So we tested the existing fee against an all-inclusive price. Same total cost, just no fee language. The test showed increased abandonment with any mention of a fee, no matter where it was in the process. We modeled the impact and showed fees had likely cost the company a few million dollars a year, far outpacing any benefit. Yet somewhere along the line, a spreadsheet was undoubtedly produced and updated to show how the fees led to X-point-Y percent incremental revenue growth. But it couldn’t capture the negative consequences, because this group didn’t know they existed. A serious blindspot was created because it never occured to them to discuss the issue with customers.

But what seemed like clear-cut evidence, with an easy path to higher revenues, landed like a bug on a windshield. What we never imagined was that internal goals had sprung up around fee revenues. Or that correcting the issue would result in a reporting shortfall because you’d no longer be pulling forward revenue. And, of course, senior leaders behind fees resisted backtracking on their direction. In the end, the fee was phased out, but it took them almost a year to untangle the conflicting priorities.

The experience reinforced how complex the internal stakeholder web can be, and why you may need to look beyond your specific division or department to drive lasting change.

Design thinking is really just creative problem solving

Q. You mentioned design thinking earlier. What happened to it? I remember when there was a huge amount of buzz around it, maybe ten years ago: cover of Harvard Business Review, design program at Stanford in partnership with Ideo. Design thinking as the mental paradigm for the future, the way everybody’s going to be organized. And then from the outside it feels like it almost evaporated. Is that fair, and if so, what do you think happened? What do you think its status is today?

A. In some respects, I think Design Thinking has been a victim of its own success. If you’re familiar with the Gartner Hype Cycle, we’ve definitely passed the Peak of Inflated Expectations. A lot of people are stuck down in the Trough of Disillusionment, but some have come back up, and are learning to make productive use of Design Thinking principles.

And that’s a key point, we’re talking about principles, or a perspective, not a process. The activities people associate with Design Thinking are intended to tease out and test our understanding as a way to manage ambiguity. It wouldn’t make sense to be a formula, but people crave structure.

Rightfully so, IDEO gets a lot of credit for packaging its design instincts for mass consumption. Design Thinking gave people the structure they needed to comprehend what was happening in the minds of great designers.

But if you track the elevation of design in business, you have to start with Apple’s incredible comeback under Steve Jobs. He deeply understood the value of design but had no reason to make it accessible. Instead, Apple leveraged design’s mystique to its advantage.

Competitors tried desperately to copy them, but design was infused into Apple’s culture from the top down. And, by contrast, it was that industrial-era perspective of legacy MBAs driving culture for those competitors. By its very nature, design is antithetical to that worldview.

IDEO, on the other hand, is a design consultancy that benefits greatly from being seen as the experts they are. And they’re smart enough to know that expertise isn’t easily copied, so they had no problem being transparent about their process. Basically, “If you can make it work, good for you, if not, hire us!” It was a freemium approach to design consulting. And for a lot of agencies now, it’s a core aspect of their content marketing strategy.

Apple’s high-profile success created a broad desire for great design, and IDEO rode that wave perfectly. No surprise since Steve Jobs and David Kelly had been close friends for a long time. Design Thinking opened the door for designers like me to have a role in strategy, but you’re not wrong that it has largely disappeared from business media. Despite being an evangelist for those principles myself, I generally avoid the term just based on the current perception. However, I wouldn’t say it’s evaporated, so much as the core message has now infused itself into best practices around customer experience.

Not long ago, large-scale surveys and focus groups were the gold standard of customer research. Now it’s generally accepted that companies engage in ethnographic studies, iterative user testing, and unstructured qualitative research. Forward-thinking businesses understand that these practices are part of a creative problem-solving process. That’s all Design Thinking ever was, and it’s more relevant than ever.

Agile should not be waterfall with sprints

Q. I want to share a slightly different spin on design and agile that I hear sometimes, and I want to get your reaction to it. I get cases where agile is presented to me as the enemy of design in the sense of, “they’re doing two week sprints, and I’m the designer, and they tell me to draw them a pretty picture. ‘You can do that in 2 weeks, right?’ And I say no, I need to go off and do research, and I need to test prototypes, and they say, ‘No, the engineers are waiting. Just draw us a pretty picture, and we can go do this.’”

A. Yes, I’ve definitely run into this, too. In principle, good design and agile go hand-in-hand, but they’ve both been distorted in the interest of predictability. Just as agile is too often waterfall in sprint form, designers are seen as the “pretty picture” people. The assumption is all too common and it fundamentally underestimates the role of design. Unfortunately, it’s typically baked into the way organizations build teams, manage projects, and set goals.

I think the root issue is that design is seen as a downstream process, after product goals and schedules have been committed to. If you want to maximize the impact of design to improve customer experiences and business outcomes, leverage design research to establish an insight-driven foundation, then allow design sprints to advance that knowledge over time, long before touching code.

After all, it’s a lot easier to explore user needs with pixels. Being in code without that understanding is just asking for costly revisions or a bad user experience because you’ve skipped sensemaking. Ideally, once the foundation is set, user research and design are working a couple of sprints ahead of development. That way product testing and design revisions are about refining your understanding, not building it.

Democratization means “this is important”

Q. Let’s talk about democratization. That word is a red flag to some people. Do you have a favorite term for it? Some people say scaling. Some people say other stuff. Before we even get to talking about what it is, what word would you use for it?

A. Oh, boy… Yeah, “democratization” has been thrown around a lot in product over the last few years. There seems to be a fair amount of confusion as to what it means, along with a sort of protectionism that I find counterproductive. I do like the notion of “scaling research,” because it elevates the role of research within an organization. Jen Cardello offers the clearest vision on this that I’ve seen, but I don’t think it covers what democratization aspires to.

Ultimately, I don’t get to pick a new label, so I’m more focused on what it means to others. I’m personally encouraged by democratization, if only because there’s a history of how the term gets used in the business world. Go back through HBR over the last couple decades and you’ll see that the cloud democratized computing, data science democratized data, and so on. It’s about taking what is a priority for business and making it available across an organization.

Democratization gets used because it’s accurate, so I’m not really interested in alternatives, but I know it’s a red flag for some researchers. Personally, I think they should be celebrating. I’ve certainly faced the challenge of research being ignored and underfunded, and heard similar stories from others. Then here’s a shift in business priorities saying research has such broad value that “democratization” is the goal. So to those researchers who say, “Do you want your job democratized?,” I say, “Yes, absolutely.”

I would love to have more people involved in making informed design decisions. That would mean that design is a priority within the business. I used to say that AAA didn’t have just a handful of designers, but hundreds, and we’re just not giving them the support to do it well. Anybody who impacts the customer experience is making a design decision. Every day, they choose one path or another based on somewhat ambiguous and subjective information, but they don’t see this as design, it’s just “the job.”

That’s because design usually gets spoken about in the noun form, as the artifact being created. It’s the UI, fashion, interior, or some other downstream output. But that’s just the result of a much larger process, design as a verb, which is to craft something for a particular intent or purpose. The verb form of design is something that all of us are engaged in on some level, but don’t connect with our job because “design” isn’t in our title.

Design usually gets spoken about in the noun form, as the artifact being created, but that’s just the result of design as a verb, which is to craft something for a particular intent or purpose. All of us are engaged in design on some level, but don’t connect it with our job because “design” isn’t in our title.

Of course, there are specialists within design, but it’s a process we’re all involved in. And I hope more people get involved. I think that was the highest aspiration of Design Thinking, so I would love to democratize design and research as much as possible. I mean, data science has been one of the fastest-growing occupations for years because people realize how important those insights can be. But if nobody used data unless they were a data scientist, part of a group of math wizards in some corner of the building, what good would that do? This is definitely a “rising tides” situation for designers and researchers, so I think it’s important to embrace the change.

That’s not to dismiss the risks associated with amateur research. After all, you don’t want to introduce bad knowledge into an organization, but the reward is worth correcting for it. This is where an agile perspective comes into play.

Strategically important research should be carried out by specialists, just as UI specialists produce the visual layer for a product. But there are a number of things that can be course-corrected on a regular basis. And so the risk that’s inherent to involving more people in research is mitigated by having tighter cycles, but only if you take a posture of continuous learning.

So I don’t think the democratization of research is going to reduce demand for research specialists, or muddy the process. I think it’s going to elevate the visibility and impact of research within organizations. And, most importantly, it’s going to change the perception of qualitative insights, which is what currently holds back their influence.

We spend a lot of time staring at one side of the data coin, rarely turning it over. Broadly speaking, organizations are dangerously overinvested in quant. Which, of course, offers a significant opportunity for companies willing to pursue a more balanced approach. And that’s where you see disruptors enter the market, so companies ignore human insight at their peril.

Q. So I think you’re saying that the ultimate goal here is not democratizing research, it’s democratizing design – with design being writ large as a certain way of relating to customers, and making sure anything that touches them is well thought out. That includes developing empathy and getting feedback from people. And the reason you want to democratize the research is because you’re trying to drive good design practices throughout the entire company’s decision making. Is that fair?

A. That’s a fair assessment, but as a product designer, that’s certainly my bias. Design, by its nature, is intended to be holistic, and research is what powers good design. So if involving more people in design is democratizing design, and to do that well requires research, then you’re democratizing research, too. If you want to elevate the design maturity of the organization, you’ll have to value design research.

If involving more people in design is democratizing design, and to do that well requires research, then you’re democratizing research, too. If you want to elevate the design maturity of the organization, you’ll have to value design research.

And that’s not to say that everyone needs to have design specialist-level expertise. An appreciation of design’s larger contribution would be a great start, as would valuing qualitative insights alongside quantitative data.

Foster a culture of learning

Q. Is there anything else that you want to be sure we touch on?

I’ve talked a lot about research today, so it’s important to acknowledge that I am not a trained researcher. I’m a product designer who leverages qualitative research to solve business challenges. But I think a big part of my success has been that I approach research as an iterative process, so I would encourage researchers to build toward understanding instead of trying to arrive there.

There’s a preoccupation in business, and perhaps American culture broadly, with getting things right the first time. I’ve worked with researchers who spend a lot of time trying to eliminate all bias, crafting perfect questions, and generally trying to exercise as much control as possible. I see that as a waterfall approach to research that assumes you’ll achieve certainty at the end of the process.

I’d rather run three times as many imperfect tests that open the door for serendipity and refinement. Countless times I’ve had an imperfect question get interpreted in a way that opens the door to insights I didn’t know to dig for. Real life is messy, so there’s always going to be a margin of error, and it’s usually larger than we admit. I think research needs to be just as agile and iterative as design is.

Researchers have an important role to play in fostering a culture of learning, but they need to be generous with their skills and perspectives. They can help organizations understand that insight isn’t absolute and forever, so you’ll need to keep learning.

And even when we think we know something really well, the market will shift, driven by competitors or new consumer expectations. You want to be the company driving change in the market, but you can’t until you put human insight on an equal footing with your quant data. That’s where a lot of organizations, and legacy organizations in particular, get into trouble, by being too focused on optimizing their spreadsheet bias.

About CXI Labs

Q. Talk to me about what you’re doing now. What sort of services do you provide? How should people engage with you?

A. My experiences across AAA, and various freelance projects, showed me how pervasive and problematic issues of design maturity are. A lot of otherwise successful businesses struggle to integrate human insight into their operations, instead relying on what amounts to guessing. And a lot of product teams and leaders are getting burned out fighting uphill battles, despite being very close to the customer. I’d seen the benefits of improving design maturity first hand, so with what felt like a mission, CXI Labs was born.

I like to say we connect the dots that drive results, as that’s a fundamental challenge for a lot of organizations. Very often, it can be difficult to see or relate what can appear like disparate ideas when you’re in the thick of it. And, as I’ve said before, it can be difficult to get broad buy-in for qual insights even when connected to quant data.

We offer strategic design services to help product teams check their blind spots, get unstuck, or scale their operations, with a particular passion for helping them elevate design within their organizations. I’ve always felt like design and research, or product teams broadly, aren’t given due credit for their impact on the business.

Operations, sales, and marketing certainly drive business, but the business wouldn’t exist without the product. Long before social media, Peter Drucker offered sage advice about knowing the customer so well that the product sells itself. And as anyone who’s ever read or written a review knows, that’s more true now than ever.

Our aim is to exceed business goals by crafting product experiences that so completely meet customer needs they can’t help but talk about it. And when companies work to improve their design maturity, that becomes a sustainable advantage.

If someone out there is facing a customer experience innovation challenge, we’d love to be of service. They’re welcome to find us online or email me directly: james@cxilabs.com.

Q. Okay, so if you’ve got somebody in an org where they are trying to do that — leveling up their empathy and stuff like that — are you the guy to bring in to help them work through that process and make that happen within the organization?

A. I’ve certainly got some hard-won lessons to share, and as much as I love improving products, empowering change really fills my cup. I enjoy working with product teams and leaders who are looking to disrupt the status quo. Those are the sorts of people who have the passion required to drive the evolution of an organization.

Image courtesy of Dall-E 2.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of UserTesting or its affiliates.

Table of contents

- The path to design

- Good design means embracing ambiguity in business

- How to create change in an organization

- Why innovation labs fail

- Evolving the AAA home page: The benefits of focusing beyond price

- Learn empathy for your internal stakeholders

- Design thinking is really just creative problem solving

- Agile should not be waterfall with sprints

- Democratization means “this is important”

- Foster a culture of learning

- About CXI Labs