Table of contents

- Why companies care about scaling insight

- How to make scaling work

- Four steps to scale scale human insight

- Step 1: Agree on the goals for scaled insight, and create a plan to roll it out

- Step 2: Decide how you’ll control the quality of the tests

- Step 3: Drive adoption by non-researchers

- Step 4: Transform the role of the research team

- Conclusion: The path is clear

- Additional resources

This guide is for managers who are looking to scale human insight by empowering non-researchers to run their own experience tests. We’ll cover the steps to take, challenges you’re likely to face, and best practices. We’ve also included four real-world stories from companies that scaled. This information is based on our experiences with hundreds of companies running scaling and democratization programs.

Summary

What would it be like to have a customer sitting next to you 24/7, so you could instantly ask them any question or learn how they think and feel about any idea? What if that feedback was available to every person in your company? How much smarter would your company be, and how much faster could you move? That sort of continuous human insight is a fundamental improvement in the way companies make decisions.

The next step beyond agile. Agile business principles say the best way to delight customers is to fail fast: try a lot of things and wait to see which ones succeed. But you can move even faster if you don’t fail in the first place. Many product and marketing teams are reaching a higher level of productivity by empowering non-researchers to validate customer needs continuously and insert rapid human insight into every stage of their work processes. Companies that scale insight in this way make more money because they iterate faster, do less rework, and please customers more thoroughly than their competitors.

But it’s not easy to make a scaling program work. Changing work habits is hard, and it’s distressingly common for companies to run into executional and political barriers when they try to scale insight. This document will help you guide your scaling process to success.

Why companies care about scaling insight

Let’s start with a definition: When we talk about “scaling” human insight, we mean empowering people in human-facing roles — including design, product management, and marketing — to run their own experience tests continuously, informing and validating their work in real time. Some people call this “democratizing” insight. Whatever term you use, the idea is that if you broaden the number of people who can run tests, you can insert human insight into far more decisions. Employees in customer-facing teams like product and marketing can ensure that their work resonates with customers, and they can catch and correct any errors very early in development, when they are much easier and cheaper to fix. And they can do all of that at full speed, without slowing down the business.

Guessing is more unreliable than we realize, and we do it all the time. This sort of continuous human insight is attractive to companies because guessing or using “gut judgment” about customer reactions puts the company at risk and wastes money and time. Human beings are complicated, and it’s very hard to accurately predict how they will react to a feature or message. Most people know there’s some risk that they will guess wrong, but few people realize how big the risk is. The disturbing reality is that the large majority of guesses that companies make about customer reactions are wrong.

Optimization teams have studied the effectiveness of guessing for years, and they’ve found the same pattern over and over (link):

- Quicken Loans: “I can only ‘guess’ the outcome of a test about 33% of the time.”

- Slack: Only about 30% of monetization experiments show positive results.

- Google: “80% of the time you are wrong about what a customer wants.”

- Netflix: 90% of what they try is wrong.

- Etsy: “Nearly everything fails.”

Researchers at Microsoft wrote:

“Features are built because teams believe they are useful, yet…the reality is that most ideas fail to move the metrics they were designed to improve.”

We’ve built guessing into our business processes because it isn’t possible to use traditional research to vet most decisions:

- About 2/3 of design projects receive no research support

- More than half of product managers say they frequently have to guess how customers will react to a new feature

- The majority of marketing deliverables are never vetted with customers before they go live

Source: UserTesting CX industry survey

Agile development philosophy says that’s okay, because you can just fail fast: try something, measure its impact, and then iterate. That will indeed let you evolve toward a better solution…eventually. But since most guesses are wrong, you’ll waste an enormous amount of money and time along the way. The economic impact is huge:

- Avoidable rework is estimated to consume 40%-50% of the product development budgets, according to the USC Center for Software Engineering (link).

- Product management consultant Rich Mironov estimates that 35% to 50% of software development costs are rework due to inadequate discovery (link).

As an alternative to guessing, companies could build out a research team that’s large enough to test every decision. But most companies can’t afford that, and are choosing an alternative: They empower people in product, marketing, and other customer-facing roles to test their own work, while they have the research team focus on strategic issues.

A better lifestyle than failing fast. Companies that adopt this scaled approach to human insight have a competitive advantage because they increase their odds of making a decision right on the first try. They save money, and even more importantly, they can optimize their products, marketing messages, and other experiences faster than competitors who use old-school “fail fast” processes.

Scaling doesn’t mean death for the research team. Research teams often feel threatened by scaling. They worry that they’re cannibalizing their own jobs, and they are deeply concerned that the quality of research will be destroyed. Those risks can be minimized. In fact, research teams that scale successfully are finding that scaling makes them more influential, more strategic, and more central to the company’s success. It’s a big change, but it can be a change for the better.

How to make scaling work

Successful scaling requires you to make changes throughout the organization, not just in research. You have to adjust the roles, expectations, and work processes of people throughout your company’s human-facing teams. The workers need to learn new reflexes, and senior management needs to adjust their incentives. This process transformation yields some immediate benefits, but fully maturing your process takes years. That means you need long-term executive support, a well-built plan, and realistic expectations.

Based on what we’ve learned from companies that scaled successfully, there are four steps you should take:

Four steps to scale scale human insight

- Agree on the goals, and create a plan to drive the change. Scaling needs to be applied in multiple departments and management levels in the company, each of which has its own unique perspectives and needs. What looks like success to one team may look like failure to another, creating conflict that wastes time and employee energy. You need to understand those differing perspectives, build them into your program, and drive broad agreement on your goals and how you’ll measure success. If you get the planning and motivations right, you’ll prevent a lot of problems later.

- Decide how you’ll ensure the quality of tests run by non-researchers. Modern experience testing tools are increasingly fast and simple to use, but like any powerful technology, they can be misused. Even with the best of intentions, non-researchers may do poor quality tests or misinterpret their results. To maximize insights and minimize mistakes, you need to plan in advance for how you’ll ensure the quality of tests run by non-researchers. Those management processes need to be customized to your company’s culture and org structure. One size doesn’t fit all.

- Design a playbook to drive adoption by non-researchers. Designers, product managers, and marketers all have very demanding roles and rarely have a lot of spare time. Getting them to make time for testing, no matter how great the benefits, is always difficult and time consuming. You need to start small and create a multi-stage program to manage and incent adoption of human insight.

- Evolve the role of the research team. To take full advantage of these changes, you need to also replan the roles and responsibilities of the experience research team. Most researchers are used to working as a service group that does projects; in the world of scaled insight they need to grow into facilitators, supervisors, and strategic thought leaders.

Here’s more detail on each of the steps, including points on what to do and some real-world examples.

Step 1: Agree on the goals for scaled insight, and create a plan to roll it out

The idea of scaled insight is usually attractive to most people working on customer-facing projects. Who wouldn’t want to have continuous customer feedback to inform a decision or validate a design? But beyond the basic feeling that fast feedback is good, different teams in the organization almost always want to use it in different ways, to solve different problems. Often there are also different expectations between senior management and the front-line employees doing the work.

It’s important to take all of these needs and expectations into account when you design the scaled insight program. What is human insight? What problems does it solve? What processes will be affected? What’s the timeline? How will we measure success? All of these expectations need to be aligned so you won’t have disappointments later.

Here are the desires and expectations we see most often when companies scale insight:

Expectation 1: Executives want the company to become more customer-savvy and efficient. Let’s start at the top of the organization, with the people who pay for the scaled insight program. Senior executives usually sign off on these programs because they expect that rapid and broad customer feedback will make the entire company more empathetic to customers, improving the quality of everyone’s work. Almost always the execs also expect this will save money by reducing rework, and increase customer satisfaction and loyalty by driving better experiences.

Those goals are all achievable, but they require executive involvement and sponsorship to make them happen. Like any other process transformation, scaled insight works best when senior management celebrates successes and enforces new workflows. The execs also need to balance enthusiasm and patience; although you can get immediate benefits from scaled insight, even the most successful programs take multiple years to fully mature.

Frequently we find that executives assume the process will take less time, and require less personal involvement from them, than what’s needed in reality. Unless their expectations are set properly, they may decide the transformation is a failure when in fact it’s just going through predictable growing pains.

Frequently executives assume the process will take less time, and require less personal involvement from them, than what’s needed in reality. They may decide the transformation is a failure when it’s just going through predictable growing pains.

That’s not to say your company won’t see some immediate benefits from scaled insight. Even if you only transform one step in the dev process at first, or only ten percent of your non-researchers embrace human insight at the start, that is still a considerable increase in customer understanding and it will make the company more effective.

You should also be aware that, on this issue, there’s often a subtle difference between the thinking of executives and lower-level employees. Often the execs are acutely aware of the amount of rework the company is doing and the need to reduce it. This can come across to lower-level employees as a general distrust in their decision-making skills. As one exec told us, “the team is always confident, but what if they get it wrong?” The execs may rightly view scaled insight as a way to quality-check the work of their teams.

In contrast, most project teams — because they are run by confident and experienced people — don’t believe there’s a high risk that they will make bad decisions. They’re often more concerned about others in the company, including execs, failing to align with their plan, or imposing unrealistic demands on their project. So they will tend to view human insight as a way to make high-quality decisions that are easy to defend against challenges. It’s about shielding the team from distractions and misalignment.

There’s truth (and a little mistrust) in both perspectives. When rolling out a scaled insight program, it’s best to acknowledge the various motivations and show how the process addresses all of them.

Expectation 2: The researchers want to become more strategic. By handing off evaluative research (things like simple prototype tests) to non-researchers, the research team usually expects that it will free up time to focus on more strategic “generative” research that can drive big breakthroughs for the company. Many researchers find this sort of high-impact work very satisfying – and, let’s be honest, many of them also hope that doing more strategic work will advance their careers and protect them from layoffs

Often, research teams find that it’s more difficult to become strategic than they expected, for two reasons:

- As a part of scaling insight, the researchers need to spend time training non-researchers and supervising their tests. Often this consumes much of the time savings that the researchers were hoping to divert to strategic work. This problem is most acute at the start of the scaling process.

- Becoming more strategic is not like flicking a light switch. Researchers usually need to change their own behaviors and skills, and build a deeper understanding of how business leaders make decisions and the issues they care about. This process requires time and retraining. The research team also needs to create deeper relationships with other parts of the organization, particularly product management and senior management. Getting a seat at the strategy table takes time. We’ll say more about this process in Step 4.

If the researchers have not planned for these issues, they are likely to end up frustrated and discouraged when scaling insight doesn’t immediately yield the benefits they expected.

Expectation 3: Designers want to get more influence. Most designers will tell you they want more research support in the design process. That seems straightforward at first glance, but it’s important to ask why they want more research. There are usually two needs mixed together:

- Modern design processes require customer insight. Although non-designers often assume that design is mostly about creating a pretty picture, designers usually focus heavily on understanding customer needs and personalities in order to solve problems in a delightful way. Early and continuous customer feedback drives the design process, so designers are usually hungry for it, in greater volume than most research teams can deliver.

- The less obvious motivation is that designers often struggle to persuade the company to implement their designs accurately. For example, they’re often second-guessed by others in the company who have different tastes, or the engineers may advocate for a different product design that is easier to implement. Most designers find that saying “trust my vision” isn’t very effective in countering these objections, but documented user feedback can be.

So for a designer, human insight often plays two roles: It drives their decision-making, and it also defends those decisions. The design of a scaled insight program needs to take both motivations into account, by making it easy for a designer to attach evidence to decisions and share insights.

Expectation 4: Product managers want to get better alignment with less delay. The central dilemma of most product managers is that they have huge responsibility but very little formal authority. They’re tasked with leading the work of people who don’t report to them and who they can’t fire, and they’re also expected to make sure that team delivers its work on time. Therefore, aligning the team around a shared vision for the product, and protecting the team from distractions during development, is usually their most critical need.

Fast human insight is appealing to product managers because it lets them quickly gather the evidence they need to make a good decision, explain it to the team, tie them together, and resolve any disputes or questions that come up during development. It’s a very efficient way to keep the project on track. As in the case of design, this means the scaled insight process needs to make it easy to share insights and the evidence behind them.

Expectation 5: Marketers want to know what resonates. There’s an old saying that half of the money spent on advertising is wasted, but no one knows which half. That saying reflects the uncertainty of most marketing efforts: it’s very difficult to know in advance which messages and creative approaches will resonate with people. Because traditional customer research is expensive, it’s not available for most marketing deliverables. They’re launched in the blind, and marketers hope some of them will work.

Fast human insight is appealing to marketers because it injects more certainty into the marketing process. Creative work can be checked, problems identified in analytics can be diagnosed, and waste can be reduced.

Expectation 6: Non-researchers often underestimate the amount of effort required to do a useful test. It’s very common for designers, product managers, and other non-researchers to be very excited about doing their own tests at first, but then lose enthusiasm once they understand the effort required to complete the tests. The most common issue is the time needed to analyze test results.

Non-researchers already have full-time jobs. They can take on a little more work in order to get higher quality and productivity, but if the workload is too large they will disengage and go back to guessing about customer reactions.

It’s possible to overcome this adoption inertia through preparation and training. Test templates and AI can make it much easier to analyze test results. Many companies also mandate that projects can’t get past certain stage gates unless customer tests have been run. This is one of the reasons why ongoing involvement from senior management is so important; you usually can’t change a process unless the execs actively support the change.

We cover this issue more below, in Step 3.

Expectation 7: Everyone assumes that test quality will be great. In many of the scaled insight programs we’ve seen, the company assumes that the newly-empowered non-researchers will do high quality tests. Successful scaled insight programs do not make this assumption. They acknowledge that good testing needs good quality control, they provide extensive training for people who are new to testing, and/or they create process guardrails that restrict bad testing (this can include restricting the test methods available to new users, and requiring checks on their tests before they are launched). We’ll discuss this issue more in Step 2.

Successful scaled insight programs also acknowledge that different levels of quality are required for different types of test. For example, testing the prototype for an informational web page is relatively simple to do, and has limited risk for the company’s overall revenue. It needs less quality control than a market segmentation study that might be used to drive strategy for years.

Quality issues should also be considered when you plan how you’ll share research insights within the company. Some companies want to share all research findings broadly, usually through an online insights hub, in order to maximize efficiency. On the other hand, some companies deliberately exclude from the hub any test results created by non-researchers. This is to prevent the occasional flawed test from going viral within the company. Either approach can work, but you should make a conscious decision about it now.

These quality-control tradeoffs are often very painful for research teams, because researchers take professional pride in making every piece of research as perfect as possible. Asking them to help others run tests can feel like asking a Michelin-starred chef to serve fast food. You need to constantly remind yourself of the alternative: non-researchers today are making many important decisions based on hunches, anecdotes from unreliable sources, or things they found on the web. As long as a test is better than their current pattern of guessing, it’s an improvement for the company, and should be viewed as a win. Over time, you can further improve the quality of these tests through additional training and by building a culture of good testing practices across the company.

As long as a test is better than their current pattern of guessing, it’s an improvement for the company, and should be viewed as a win.

Your executives need to buy into this balancing act on quality. We’ve seen cases in which an exec saw one mediocre test and decided that the whole scaled insight program was out of control. There are tradeoffs in any business process, and when you broaden insights you are accepting an occasional mediocre test in order to get a much higher level of customer understanding overall.

Action plan

The first step is to recognize that you’re driving a change process, and change needs to be planned. There are many good books and whitepapers on how to drive change in an organization; we won’t repeat all of their content here. But a resource that we think is especially relevant to scaled insight is Deloitte’s whitepaper on how to architect an operating model for digital transformation. The first part of the paper is theoretical, but pay special attention to the recommended actions on page 11.

Here are the process steps that we’ve seen companies use to align expectations around their scaled insight program:

Identify an exec sponsor and a program leader. The program leader, sometimes called the champion, is a senior individual contributor or manager who can devote most of their time to driving the scaled insight program: changing processes, teaching, documenting agreements, promoting the program, and creating and managing the transformation schedule. Sometimes a couple of people are assigned to this responsibility, but at a minimum you need one experienced person who has very little other work on their plate. The right champion should already have some respect in the organization, and enough business experience that they can negotiate meaningfully with managers, directors, and VPs.

The scaled insight program leader also needs good communication skills. Their role isn’t just to run the program, but to facilitate communication and create energy. In some ways it’s an internal evangelism role, and the program leader needs to be comfortable with that.

This is absolutely not the sort of role to assign to an intern or a new hire just out of college.

The executive sponsor needs to be someone who controls a significant part of the organization, and who has personal access to its top levels (to the CEO in a smaller company, or the general manager in a larger one). Usually the sponsor is a C-level executive or VP. Sponsoring the scaled insight program is not a full time role, but the exec needs to be available on short notice to provide guidance and political air cover to the program leader. The exec sponsor should also be a vocal internal cheerleader for the new process, celebrating employees who are doing a good job of using human insight and reminding everyone that the process is not optional.

Do a listening tour. The program leader should meet one on one with key stakeholders in the human-facing teams. The listening tour isn’t the time to pitch the new process; it’s an opportunity to understand their issues and motivations, so that you can create a process that meets their needs. Your goal is to get them talking and ask them good follow-up questions. Here are some questions to ask:

- What are your top goals for the year?

- What are the biggest barriers to achieving the goals?

- How do you know that the experiences you’re creating are good?

- If you had a magic wand and could make one change in the company, what would it be?

- How do you feel about the company’s current flow of customer insight? Is it relevant to your needs? Do you get enough of it, when you need it?

- How often do you have to guess about customer needs or reactions?

Try to get them talking about not just the business issues, but how they feel about them. Some people don’t want to go there, so you shouldn’t push, but change is both a logical and an emotional process, so the more you understand about how people are feeling, the better you can guide the transformation.

The other reason for the listening tour is to create channels of personal communication between the program leader and the stakeholders. The more trust you create at this point, the easier it will be to resolve problems later.

Create and share the plan. Once you understand everyone’s perspectives and hot buttons, the program leader should create a written plan for the transition (either slides or a full written document). The plan should include goals, measurements of success, timeline, changes to current processes, budget, and a list of key stakeholders.

The budget should include two items:

- The cost of the testing tool(s) that you’ll be empowering the employees to use

- A services budget to cover the assistance you’ll need to set up and manage the program (see Step 2 for details). You might believe that you don’t need any outside help to set up the program, but usually that’s a fantasy. Read through all the tasks we describe in this document, and be very honest with yourself about whether you have the capacity to do all of them in house.

Review the plan privately with the exec sponsor first, and then the stakeholders, before you present it more broadly. Be sure everyone is on board, especially including the managers of the non-researchers who will be doing tests, and the people running the processes you are changing. They all need to feel like co-designers of the process or they may not give it the support it needs.

This planning process sounds elementary, but you might be surprised by how many companies scale insights one person at a time, without any supervision or quality control. That can work if your company has a very ad hoc culture, but in most companies it can create confusion, low adoption, and frustration that some employees are operating differently from others.

Start small. Because human insight can improve the entire product and marketing life cycle, it’s tempting to deploy it broadly, for many problems at once. That can be done, but the bigger your transition, the more work you’ll need to put into planning it, and the more risk of things going wrong. We think this is a good place to borrow from the principles of agile development: Make a single change that you can implement fast, see how that works, and iterate.

In the case of scaling insight, that usually means empowering non-researchers for a single kind of test or a single phase in the development life cycle. The most common starting points are either testing prototypes or doing discovery interviews, but the best thing to do is choose any situation where the company is feeling a lot of pain and you can demonstrate benefits quickly. That will help you create momentum for further change.

Create some sort of steering committee. You don’t necessarily need a formal Steering Committee with assigned members and scheduled meetings; that depends on your company culture and how dispersed the organization chart is. But at a minimum you should have an informal network that connects the insight program leader with the stakeholders from the listening tour. This group should communicate regularly to track the progress of the scaling program, make adjustments, and nip off problems before they become serious. Progress should be reported to the exec sponsor regularly. Let the sponsor ask questions, and give them examples of successes and insights the program is generating, they can share them with the company’s leadership.

Profile: A services company evolves a controlled approach

A major business services company had a problem with too much demand for experience research. There were far more requests than the research team could handle, so they created a triage process to prioritize the most important tests. The remaining requests for research were turned away.

That disturbed senior management, which asked what the research team could do for the projects that they turned away. So the research team created a “do it yourself” program that empowered designers and product managers to run their own tests. The research team created some lightweight training and held office hours so designers and PMs could ask for help if they wanted it. Otherwise their activity was unsupervised.

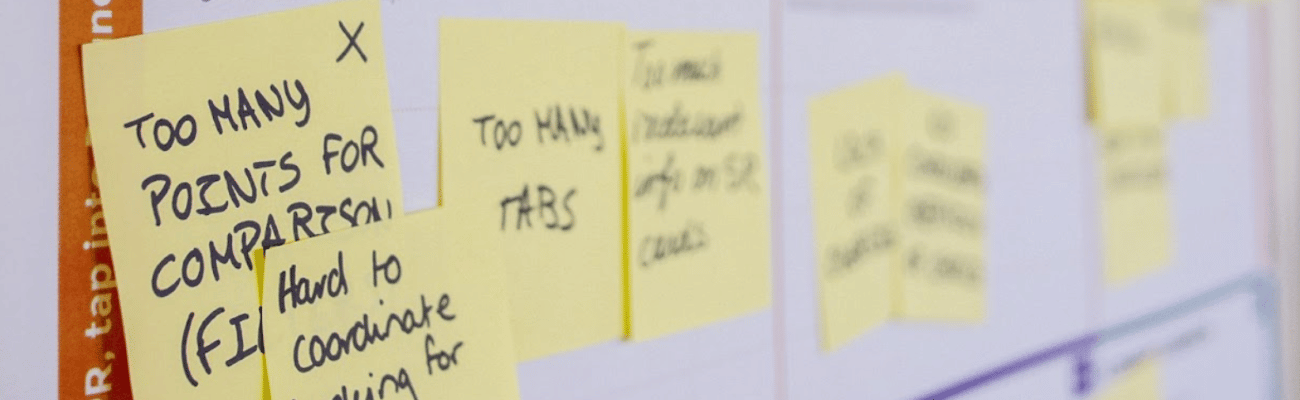

This eliminated complaints about lack of support. However, a couple of years later, senior management noticed that a lot of very poor quality tests were being run by non-researchers. They worried that the company was making bad decisions based on this research. The research team was tasked with solving the quality problem. They modified the do-it-yourself program:

- First, they tried to create more extensive training for the non-researchers, including classes run by both the research team and the vendor of the insights tool. The company also ran lunch and learn sessions with internal and external speakers on how to do tests.

- The training helped some, but was not enough to resolve the problem. So the company created formal guidelines on what sort of tests non-researchers can do. Non-researchers are allowed to do basic evaluative tests (like prototype tests) and customer interviews. Complex studies involving user flow through an important part of the website, or questions that will drive major decisions by the executive team, require participation by a researcher.

- The research team also created test templates, along with detailed documentation on how to use them

- Study results from the research team are shared broadly in the company through a research archive, but generally the test results from non-researchers are not shared because they’re viewed as less reliable

- To enforce the testing rules, the Approval Flow feature was turned on, so no one could launch a test unless it was checked by a researcher.

- Because Approval Flow is the main mechanism for quality control, the team no longer mandates heavy training. Self-guided information is available, and non-researchers are generally expected to learn the basics of testing through their peers and managers.

We have changed our school of thought. Do it yourself is still needed and necessary. We’re a lot more comfortable with UX designers DIYing than with, say, our marketing or product managers. And it’s not because those people can’t DIY, it’s because the questions that they’re trying to answer more often are far more complex. I have some product managers and some product marketing managers who I’ll enable to do their own interviews any day of the week because they’re very good at it. But there is a tipping point where they shouldn’t be doing it anymore, because the question is too complex.

Senior Director of Customer Research

With the time it has saved by empowering others to test, the research team has focused on delivering strategic information to senior management. It partnered with a C-level executive to feed a steady flow of research insights into the C-team’s Slack channel.

Step 2: Decide how you’ll control the quality of the tests

Congratulations! You now have the stakeholders aligned behind your scaled insight plan. The next issue you need to focus on is quality control.

As we discussed in Step 1, it’s not possible to scale human insight and also ensure 100% perfect quality in every test. Full-time researchers usually have master’s degrees and other professional certifications, and you can’t completely duplicate that expertise in someone who hasn’t had the same training. When you scale insight, you’re deliberately accepting a little loss in quality to get a big increase in research volume and speed. To find the balance that’s right for your company, ask yourself two questions:

- How much quality risk are you willing to accept in order to get more and faster insights?

- What sorts of quality controls fit best with your corporate culture?

The answers are different for each company; what works well for one sort of company might be completely unacceptable to another. So in this section we’ll list the options, and you can make an informed decision about what works best for you.

There are two ways to ensure quality when scaling insight

We call those two approaches the Education and Guard Rails models.

The Education model relies on heavy training to teach non-researchers how to do studies. Typically they go through six or seven classes, one a week. Topics include the philosophy of research, study design, methodologies, and so on. The classes include classroom time (either by live videoconference or in person) plus homework. The homework is mandatory and is evaluated by the instructor. Participants who do not engage in the classes, or who do not successfully complete their homework, are removed from the program.

After the successful completion of training, participants are certified to run their own tests. They are given access to the testing system, and their work in it is usually not closely supervised afterward.

The Guard Rails model takes a different approach. Participants receive little or no formal training (they may attend a single class, watch a video online, or receive basic introduction from a current user). Instead of coursework, the company relies on heavy documentation and process controls to protect quality. Written step-by-step guides tell people how to run tests. Mandatory templates and predefined participant groups are usually created, along with detailed documentation on how to use them. The researchers hold frequent office hours to answer questions and coach the non-researchers. As part of the Guard Rails model, Approval Flow is usually turned on. Approval Flow prevents a test from being launched unless it has been reviewed by a researcher.

Some companies like to use a mix of both the Education and Guard Rails models — they do a lot of formal training and also implement process controls. There’s nothing wrong with that; it’s the business equivalent of wearing a belt and suspenders to hold up your pants. But in most cases, even when a company combines models, it usually leans more heavily on one of them.

Neither model is inherently better than the other. They have both been used in very successful, high-volume scaled insight programs. Which one you choose depends mostly on your company’s culture.

How to choose the right quality control model for your company

Companies that prefer the Education model are usually top-down. Employee roles are well-defined, lines of authority are clear, and everyone knows in detail what they are expected to do. These organizations run a bit like a symphony orchestra; the music is best when everyone focuses on playing their parts predictably and well. When these companies scale insight, they usually create a detailed plan for implementing it, and they scale very deliberately from researchers to designers, with the responsibilities of each clearly defined. These organizations often prefer the Education model because it fits with their controlled approach to business, and it gives more predictability about the behavior of people doing tests.

Companies that prefer the Guard Rails model are less centralized. They drive responsibility down into the organization, and expect employees to adapt their work to changing conditions on their own. These companies run a bit like a jazz band, with the performers collaborating and improvising in real time to create great music. Because they are less deliberate, they may empower people more broadly across job roles (usually both designers and product managers, but sometimes marketers as well). The Guard Rails model suits these companies well because they want to maximize their ability to make quick decisions at lower levels. (Many of these improvisational companies also have relatively high rates of employee turnover, so it’s not efficient for them to constantly run new hires through seven weeks of research training.)

To choose the right scaling model for your company, you need to be very honest with yourself about your company’s culture and strengths. Which model best matches the way you operate? Which one will be more sustainable over time?

You should also consider the drawbacks of each model:

- The Education model is expensive to scale broadly. Even the most controlled company still has employee turnover. As you empower more employees and more teams, the training burden increases. If you don’t budget for that ongoing increase in training, you may find that you need to restrict the number of people who get empowered to test, which is contrary to the whole idea of scaling.

- The Guard Rails model requires ongoing commitment from the research team. Although the Guard Rails model requires less intensive training up front, it creates ongoing work by the research team to review tests, coach non-researchers, and maintain the documentation and processes that guide scaled insight. Usually at the beginning of a scaling program this overhead consumes almost all of the free time that researchers thought they would have available to do strategic studies. The company is better off because a higher total volume of testing is now being done, but the researchers may be deeply frustrated. As people settle into their new roles, the burden of supervising non-researchers gradually declines, so there will be opportunities for strategic work eventually. But the supervision burden never goes away completely. It is a permanent change in the role of research, which we’ll discuss in Step 4.

Action plan

Don’t be in denial about the need to ensure quality. Many companies scaling insight don’t want to confront the quality control issue. They may believe it won’t be an issue for them, or they may be reluctant to add complexity to an already complex change. Usually that’s a mistake. It’s much easier to implement quality controls at the start than it is to rein in bad processes after they have taken hold. It’s also a lot safer politically to deal with the issue before some executive gets upset.

So the plan you create in Step 1 should have a section on quality control. It should define how you’ll make the tradeoff between test quality and volume of insights, identifying the level of quality assurance required for each type of test. You should also address how broadly you’ll share the insights from the tests that are run by non-researchers.

Your plan should identify which quality control model you’re using (Education or Guard Rails). You can also choose a mix of both. In addition to laying out the general approach you’ll use, be specific about the techniques and processes you’ll use. For example, how long will the training be? Will it be live or self-serve? Who will conduct it? Which guard rails will you set up, and how will you maintain and enforce them?

Assess the skills and motivation of the non-researchers. In most companies, the people you’re empowering to run tests will have very diverse levels of research skill. Some may have done research before, or may have studied it in school, while others will know next to nothing. There will also be variations in enthusiasm: Some people are very interested in learning research, while others are much less excited. The best way to assess their skills and motivation is to interview them individually, but if you don’t have time for that you can also have them fill out a quiz. Once you understand their skills and motivations, you can decide what sort of training they need, and how much supervision each individual requires. If you’re lucky, you may be able to co-opt the experienced/enthusiastic ones as coaches for the rest of the organization.

Get help with training and templates. If the volume of work required to train and support non-researchers looks overwhelming – and it usually does – you should plan to get outside help. As in any other process transformation, you can engage the vendors you’re working with, or third party consultants, to supplement your capabilities. Your plan for scaling insight should include the budget for this help.

We’ve seen companies use outside resources in their scaled insight programs to:

- Design and customize the training program

- Create and deliver training classes

- Create templates, participant groups, and documentation

- Run office hours, freeing up that time so the research team can do strategic work

- Manage Approval Flow and quality control on studies created by non-researchers

Which tasks you farm out to outside help, if any, are up to you. We find that the mix varies from company to company. For example, one company might feel it’s critically important that they create all of the templates and process documentation in-house, while another company wants that done for them.

Create a testing queue. Although you’re empowering non-researchers to run their own tests, you probably should not let them act completely on their own. Many of the companies we work with (including UserTesting itself) create a central queue, managed by the research team, of all the tests that are being done, whether the person driving the test is in research or not. The queue can be as simple as a shared spreadsheet, although we have also seen more elaborate databases.

The queue can have several benefits:

- You can ensure that the same research is not being duplicated in different parts of the company

- You can decide on a case by case basis which studies need researcher involvement. Even if you’ve created detailed rules on which types of study do and do not need a researcher, there will always be edge cases, and it is helpful to identify those projects at the start

- Most human insight systems scale their pricing to the volume of research being done. It’s important to track who is doing what so you don’t accidentally overrun your budget.

If you’re creating a queue, you need to develop a form that people will fill in to propose tests. You’ll also need to decide who maintains the list, who reviews and approves tests, and how often the reviews will happen. You will also need to write guidelines for which tests get approved and what happens if a test is turned down.

Profile: A financial services company learns to be systematic

A very large consumer-facing financial services company wanted to insert customer insights into its design process, by empowering designers to run their own validation tests. It created its own program to enable the designers, instructing them that they should run tests, and providing minimal training.

The uptake from the designers was very low. They did not know how to run the tests, and found it to be a large drag on their time. A significant number of them quit their jobs in frustration.

The company asked UserTesting to help with a more rigorous enablement program. The Education model was chosen because the company has a hierarchical culture. The result was a multi-week training program. The classes include live online instruction and homework. Once the designers complete the training they are given access to the testing tool and are trusted to do their own tests with minimal supervision.

In the first year, the program successfully trained 100 designers, and doubled the total volume of testing. The company has now scheduled training for 100 more designers in the coming year.

Step 3: Drive adoption by non-researchers

It’s ironic: Many companies put months of work into process design and training for their scaling programs only to find that their biggest barrier to success is something different: low adoption by non-researchers.

No matter how strongly the designers, product managers, and marketers swear that they want more research, and no matter how much training and support you give them, the usual outcome when you launch your scaling program is that there will be a burst of testing activity right after launch, and then activity will drop back to almost what it was before the program started. The testing activity curve almost always looks like this:

Tests (studies) per month before, during, and after rollout of a scaled insights program. Adapted from a real case.

As a rule of thumb, only about 10% of the people you train and enable to do user tests will immediately follow through and actually do them on a regular basis. So if you train 100 people, you should figure that about ten of them will keep doing it after the training ends. The other 90 will go back to guessing or whatever makeshift techniques they used in the past.

This behavior, if you don’t expect it, can be deeply troubling. The people driving the scaled insight program may feel like failures, your sponsor can get alarmed, and there might be an immediate fire drill to diagnose “what went wrong.”

In reality, there is nothing wrong. You’ve just misunderstood two things:

- The process by which people adopt change

- The deep-seated motivations of non-researchers

Let’s dig into both of those challenges.

Challenge 1: How people adopt a change in business process

If you went to business school, chances are they taught you about the adoption curve, the bell-shaped curve that describes how people adopt innovations in their lives:

The main message of the adoption curve is that about 13% of the people in any human population are early adopters who eagerly try out new ideas and products soon after they first appear. Most other people usually wait to see what happens to the early adopters before they’ll try an innovation.

The adoption curve isn’t a theory, it’s an observation of how people have reacted to many different innovations over the last century. In some situations the curve may run faster or slower, but almost always adoption of an innovation passes through a relatively small group of early adopters first before the mainstream will touch it.

Although almost everyone in businesses understands the idea of the adoption curve, they can be surprisingly slow to recognize it within their own companies. Case in point: When you roll out a scaled insight program and only about ten percent of the people you enable actually do their own research, is that a failure? No, but many companies assume it is. They need to understand that “slow” progress is just the adoption curve in action.

Your scaling plan should assume that you’ll get low initial adoption, and you should include tactics to move mainstream users through the adoption process as quickly as possible. Fortunately, there’s a lot you can do to speed them up. We’ll discuss that more in the “Action plan” section below.

Challenge 2: How non-researchers think about testing

If you’re an experience researcher, you probably chose that role because you love research: the challenge of creating a powerful study, the excitement of discovering a new insight, and the satisfaction of creating an influential presentation. When you train other people to do their own tests, you will naturally want to teach them your love of the process. Unfortunately, that usually fails.

The people who choose a role in marketing or design or product management do so because they’re attracted to that kind of work. For example, they might love the artistry of creating a message that’s compelling to the customer, or the thrill of creating a design that’s so good that the customer doesn’t even realize it’s there. Because they have other loves, they will never love research itself the way you do. It’s always going to be a means to an end.

Because they have other loves, non-researchers will never love research the way you do. It’s always going to be a means to an end.

If you want to motivate them to do their own research enthusiastically, you need to show them how it supports the things that they care about the most. Review the results of the listening tour you did in Step 1. Use your research skills to empathize with the non-researchers’ deepest concerns, and to show them how doing their own tests can help them solve those problems.

Fast in, fast out. In addition to explaining the value of fast feedback in terms the non-researchers care about, you also need to make it easy and quick for them to conduct the research. A researcher seeing the results of a new study is delighted to dive in and roll around in the data like a dog rolling on the beach, and they will do it for days. A non-researcher doesn’t have time for that; they want to get in, answer their question, and get back to their main work as quickly as possible.

That means, when you design and teach the testing process for non-researchers, you should not orient it toward doing research; you should orient it toward gathering fast feedback. What is the minimum they need to learn and do in order to get the information they’re after? Teach that and punt the rest. We’ll give you more specifics below.

Action plan

Tell everyone to expect a gradual takeoff. In your planning and communication about the scaled insight program, tell people that it’s more like an aircraft easing into flight than a rocket blasting into space. Show them the adoption curve and tell them to expect ups and downs. Your goal is to ensure that no one feels surprised or disappointed when initial adoption is limited.

Having said that, you do need to show some early progress to management. That brings us to the next point…

Focus on a single process first. It’s easier to establish momentum if you make a single narrow change to your processes first. For example, you could focus only on discovery interviews, or basic prototype testing, or optimizing AB tests. This narrow focus lets you pay close attention to what’s happening, and intervene immediately if there are problems. Your goal is to ensure that you get good word of mouth within the company (“that was easy,” “I learned a lot,” etc) because it’s ultimately word of mouth that drives adoption. Getting a quick win will also encourage the executive team to support the next stages of transformation.

Sell the benefits of human insight in terms that non-researchers care about. If you talk about the inherent goodness of great customer experience you’ll get polite nods, the same as you’d get if you gave them a lecture on healthy diet and exercise. But if you connect to the deep pain points in their jobs, they’re much more likely to lean in and get enthusiastic.

When you do your internal listening tour to kick off the scaling process, probe for places where their process breaks down, or their job is especially difficult. For a product manager that’s usually around preventing and resolving disputes, while for a designer it’s often around getting the company to follow their lead. Help them see how they can use human insight to resolve those problems.

When talking to a senior executive, the language of money is most persuasive: If they understand how you can make more money by reducing rework and driving higher customer loyalty, they’ll be much more likely to invest time and budget in the program.

Optimize the testing process for fast feedback. The biggest barrier to adoption by non-researchers is the workload required to create and analyze tests. Even if they desperately want to run their own tests, they won’t do it if they can’t fit them into their schedule. To overcome this, you need to streamline the process of going from question to answer. Here’s what works in many scaling programs:

- Create test templates plus written guides to using and analyzing them. You should create pre-formatted tests for the typical needs of non-researchers. For example, if you want to empower insights in ad testing, create templates for testing video, print, and online ads. Document the templates with detailed written how-to guides, specifying exactly what information people need to add to the template, and where to put it. Also document the process for analyzing the test results, with specifics like “look at the results from question three to understand X.” The more your documentation hand-holds people through the creation and analysis process, the higher adoption you’ll get.

- Create predefined participant groups. Screening participants is one of the most confusing tasks for a non-researcher, and it’s easy to do it wrong. You should take the screener creation process out of the hands of non-researchers as much as possible, by creating predefined participant groups for your target customer segments, and configuring your testing system so users can drop those groups into their studies easily.

- Teach the templates. In whatever training you do for the non-researchers, focus first on taking them through the templates and participant groups, and when and how to use them. This is more important than teaching research theory and general practices. If you get them to use the templates properly, they don’t need to have general research skills, and you can teach those gradually over time.

- Teach them how to use AI to analyze results. Analyzing test results is usually the single most time-consuming task for non-researchers. This is especially true of experience tests that include participant videos; most non-researchers simply don’t have time to watch hours of video. AI features can now radically reduce analysis time, by summarizing participant responses and linking directly to clips that make a particular point. You should teach non-researchers to use these AI features aggressively. Their goal is not to understand every possible insight from a test, it’s to answer their particular question quickly and then move on. Show them how to use AI to do that.

Remember: They don’t want to do research, they want to get fast feedback.

Celebrate the early adopters. You can improve the success of scaling by increasing the visibility and social standing of your early adopters. Your executive sponsor should single out the first users of human insight, praising their commitment and sharing their findings. A communications meeting is a great place to do this, someplace where the exec can praise the work and the rest of the organization can applaud.

By boosting the prestige of the early adopters, you accelerate the rate at which mainstream people adopt the innovation. Basically you’re pushing them more quickly through the adoption curve.

Hold watch parties, in partnership with the affected managers. To increase adoption further, you can hold “watch parties,” group meetings in which everyone gets together to watch and discuss videos from user tests and interviews done by non-researchers. Give them a chance to show off, and also to explain how they’re resolving the problems that were revealed by a test.

Implement stage gates. The ultimate way to get human insight adopted is to build it formally into the product and marketing creation processes. For example, the company can declare that no new project will be approved unless discovery interviews have been done for it, or that no prototype will be accepted unless it has been tested on users. Most companies that scale insights eventually create rules like this, either formally written ones or informal expectations built into the company culture.

Profile: A fast-paced tech company builds guard rails

A leading tech company is organized into a large number of autonomous business units, so it can move nimbly in many markets. One of the business units wanted to scale insight so that customer understanding would be embedded in everything the team did.

The research team in the business unit was very small, and there was a lot of employee turnover, so heavy training of non-researchers was impractical. The research team chose the Guard Rails model, and did the following:

- Created test templates, along with written guides on how to use the templates

- Created a written analysis template on how to identify and share insights

- Created moderator guides for employees planning to do live interviews of customers

- Defined what types of tests non-researchers are and are not allowed to run

- Created customized usability metrics: quantitative questions that measure usability, focused specifically on the measures that the business unit was trying to drive. The non-researchers were required to include these metrics in their tests.

- Built a wiki where test insights could be tagged and shared

- Turned on Approval Flow, so the researchers could check each test before it went out

- Created a single one-hour class on how to run tests. The research team counted mostly on shared culture, written instructions, and approval flow to enforce test quality.

The parent company had a strong culture of being customer-driven, so it wasn’t difficult to motivate non-researchers to run their own tests. They knew it would be much easier to get a proposal approved if it included fresh customer feedback validating it. The company’s decision-making culture became the ultimate incentive to test.

The research team now focuses its time on strategic projects and supervising the tests run by the non-researchers. Because of the volume of testing, the team made a conscious decision to accept some quality compromises in order to make sure there’s at least some customer input into every decision.

We want people to feel like they can get customer feedback and be customer obsessed, but at the same time ensuring a level of quality or consistency as much as possible. But also not letting perfect be the enemy of good. I tell my team, ‘I know we can see a lot of issues everywhere, but we can’t control 500 people.’ We have to pick our battles and figure out where we can have the highest impact.

Director of research

Step 4: Transform the role of the research team

As we mentioned in Step 1, part of the value of scaling insights is that it frees the research team to focus on higher-value strategic work. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. To take advantage of the strategic opportunity, the research team needs to change itself in four ways:

- Learn how to coach and support others doing research

- Change from a service mindset to a consultative mindset

- Learn to think and talk like a business decision-maker

- Create cooperative ties with the people who drive strategy

Change 1: Learn to be coaches and supervisors. In the traditional research model, a researcher’s mission is to run research projects. They control every step in the process, and take pride in their attention to detail. When companies adopt scaled insight, the role of the researchers changes. They spend at least part of their time supervising the non-researchers who have been empowered to run tests. This creates two challenges:

- The researchers must be taught how to coach. If not guided, they may try to control the non-researchers too much or too little, they may focus on the wrong issues, or they may have trouble deciding how much time to spend helping a particular non-researcher who is struggling.

- The research team needs to readjust its definition of success. If the researchers think of themselves as people who run projects, helping others will feel less satisfying and successful. You need to redefine their success as the creation of a good pipeline of research, with appropriate quality, regardless of who does the actual studies.

Change 2: Move from a service mindset to a consultative mindset. A traditional research team is extremely service-oriented: the company comes to them with questions, and the research team finds the answers. The researchers usually focus heavily on methodology, and produce academic-style reports that emphasize completeness and precision. Although they’ll include key insights as a part of their report, traditional researchers are usually reluctant to extrapolate from those insights to the actions the company should take because of them. That’s viewed as the task of the decision-maker who consumes the report.

When they think of becoming “more strategic,” most researchers picture themselves as doing more interesting and important studies, but without changes to the rest of the way they work. That is usually unrealistic. While it’s true that the research itself may become more interesting, the biggest difference in strategic research is that the researchers must have a much deeper understanding of how the business works. They can’t just run a test; they have to solve a business problem.

Strategic research needs to take into account the company’s business situation and capabilities. Often there won’t even be a clear question that the company wants to answer; instead there’s a dilemma to resolve or a new market that needs to be explored. The researcher needs to act as a business partner, understanding all aspects of the situation, formulating the right questions to ask, and devising innovative ways to answer them. Then, when the results of the research come back, the researcher is expected to translate those findings into business implications and recommended actions.

In other words, the researchers need to think and act much less like researchers, and much more like business consultants.

This change takes many researchers out of their comfort zone. It’s not something that’s taught in most classes on market research, and it may not be the sort of work that attracted them to research in the first place. So there needs to be a program to train the researchers in this new role. We’ll describe that training below in “Action plan.”

Change 3: Teach yourself to think and talk like a business decision-maker. The scientific training of researchers can limit their influence within a company, in several ways:

- Communication style. Science has a rigid and distinctive writing style that’s effective for peer-reviewed journals but seems stilted and wordy in a business setting. Academic presentations are generally long and packed with data, whereas business presentations are usually shorter and focused more on persuasion, with much of the supporting info in an appendix.

- Issues. Many researchers may be relatively uninterested in the issues that preoccupy a business decision-maker. Government regulations, competitive actions, internal politics, investor pressures, and economic changes often preoccupy business executives, but are barely on the radar for many researchers.

- Time allocation. Business executives constantly trade off competing priorities, many of them hard to quantify and based more on intuition and experience rather than hard data. They are also usually under intense time pressure, which makes them willing to accept “good enough” findings that a researcher would want to send back for more analysis.

Because of all these issues, when researchers interact with business decision-makers, they often come across as out of touch with reality, people who may be useful for a data point but are not thought partners on business problems. This becomes a huge barrier to success when doing strategic research, because the whole point of that research is to be a business thought partner.

So the training needed for a research team to scale insight isn’t just on how to behave like a consultant, it’s also about learning to be businesspeople who do research, rather than researchers assigned to business issues.

Change 4: Create cooperative ties with the people who drive strategy. If you’re going to do research that affects strategy, you need a collaborative relationship with the people who make strategic decisions. Experience researchers often have limited exposure to senior decision-makers; they spend most of their time with individual-level designers and product managers. To affect strategy, you need two-way partnership in which the senior decision-maker opens up about problems and barriers and the researcher brainstorms possible solutions. Usually these relationships need to be with director- and VP-level product managers and marketing leaders, and sometimes C-level executives. It’s a very different audience.

Action plan

Include strategic decision-makers in your listening tour. If you’re going to be a trusted advisor to experience creators and senior executives, you need to teach yourself to explain what you’re doing in their language and relate it to their problems. The best way to do that is to talk with them. You don’t have to run focus groups or full-scale ethnography on the company, but a tour of 1:1 meetings helps. You should also see if you can attend their team meetings as an observer. Ask them about their barriers to success, and what frustrates them. Get real-world examples of the problems they’ve had in the past, and what’s troubling them today. Don’t limit yourself to questions on their feelings about research; you need to understand their full business lives so you can figure out how to make your research fit.

If you’re implementing scaled insight in a product organization, put a special focus on understanding the group leaders in product management (director and VP level). They’re usually the ones who make longer-term decisions about key products and product lines, so they’re the core clients for the generative research you want to do. You need to win their trust and show them the value you can deliver. Learn their issues and feed them relevant insights quickly, so they’ll start listening to you.

The research team should meet as a group to discuss the findings from this tour and share learnings.

Become business nerds. Research company dscout describes its employees as “People Nerds,” a term we love. But if you want to become strategic, you need to become a business nerd as well. Read your company’s annual report, understand the financial pressures it’s under, check out what the competition is doing, learn this year’s goals and initiatives for the teams you’re working with, and understand how they all relate together to drive action (or not).

Then based on that understanding, figure out research projects that will address the company’s most important needs. For example, if the CEO announces that creating deeper online relationships with customers is important, can you proactively create research studies that measure online affinity for your brand, and find the levers to improve that affinity?

Train, train, train. Any business process transformation includes an element of training, to help people adjust their skills and adopt the new processes. So you need to train the researchers. Topics you should cover include:

- How to consult, including managing internal politics

- Basic business strategy

- The approval process for studies created by non-researchers

- How to teach, supervise, and coach non-researchers

Listen to the research team carefully. We rarely find a research team that’s 100% enthusiastic about empowering non-researchers to test. The role changes are unsettling, and many researchers fear that the scaled insight program is a means to eventually lay them off.

People will rarely express those anxieties out loud to management, because no one wants to sound uncooperative during a reorganization. So the fears may be obliquely expressed in other questions, or you may get the same question over and over again even though you’ve answered them before. A manager’s usual response to that situation is to slow down and repeat the same answer again, a bit more forcefully. That may not be helpful. If you’re getting confusing or repeated questions, it may be a sign that people have unstated concerns that haven’t been addressed. Repeating the same answer may make things worse.

As the leader of the research transformation process, you should slow down and listen very carefully to the comments and questions you get from the research team. Because you have been thinking about the process so much, when you hear a question, it’s very easy to assume that you understand why it’s being asked and to try to answer it quickly and efficiently. It’s better to pause and probe a bit: Why are they asking the question? What underlying problem are they worried about? You can even rephrase the question and repeat it back to make sure you understand it. Dig in and listen to see what the underlying issue is, and then address that.

Sort researchers into the roles that match their interests. Early in the transformation of the research team, you should decide how you want to evolve the roles of the current researchers. You have two options. One is to have everyone do the same role: a mix of enablement and strategic studies. So, for example, everyone spends some time doing office hours and approving studies by non-researchers, and you rotate that work among the team.

That’s certainly democratic, but it may not be the most efficient approach. The other option is to create specialist roles: For example, one person might be a full time reviewer and coach, while another might be a full time strategic researcher. The specialist approach may produce a better fit between employees and roles. Some people are innately better at strategic thinking, while others may be especially good coaches.

The downside of the specialist approach is that it can create status problems. We’ve seen research teams in which the strategic roles are viewed as the more senior and prestigious, which made the people assigned to other roles feel punished. That’s damaging to team morale, but more importantly it’s also the wrong way to look at the roles. All of them matter, in different ways. A great coach and facilitator may actually be the most impactful person on the team because they multiply the productivity of so many other people. You need to be sure all of the roles have appropriate status, compensation, and opportunities for advancement.

Adopt the “inverted pyramid” communication style. Derived from journalistic writing, the inverted pyramid flips the usual academic writing format by putting the conclusions and recommendations at the beginning, and the supporting evidence at the end. You can use this structure for both written documents and presentations.

The inverted pyramid is very useful for communicating to busy people because they can see the takeaways immediately and can dig deeper if they want to. You can see an example of the style here.

Clean up your charts. Academic research prides itself on creating data charts that include all details, the more the better. Business charts need to be so clear and streamlined that you can see the result that’s being communicated without any explanation. Any time a researcher says, “this is a complex chart, so let me tell you what it means,” that is a sign that the chart should be simplified or deleted.

To be seen as a strategist, communicate strategically. Research leaders sometimes ask us for advice on how to get “a seat at the table for strategy.” A seat at the table is earned, not given. You earn it by giving executives actionable information that addresses their hot buttons. Make sure each of your communications to them is insightful and has clear implications. Remember that they’re very busy, so it’s better to under-communicate with great insights than to over-communicate with pedestrian findings. For this reason, we’re not big fans of weekly internal newsletters. Once you tie yourself to a publishing schedule, you’ll eventually find yourself sharing less impactful information just because it’s time to publish. That rapidly erodes your image for great insights. Instead, wait until you have something truly useful to say, and then communicate it immediately.

Profile: UserTesting transforms its product development process

In 2023, UserTesting redesigned its product development process to embed human insight at every stage. The responsibilities of research, design, and product management were tweaked, employees were retrained, and new work rules were created.

The redesign was driven by the merger between UserTesting and UserZoom, two leading experience research companies. The two companies had different organizational models for experience research. UserZoom used a centralized model in which all experience research was run through the research team. UserTesting had a decentralized model in which any designer or product manager was empowered to run their own tests, with little supervision.

When the companies merged, it became clear that neither model was a fit for the new organization. There was no way the researchers could handle the full demand for testing in the combined organization, especially as senior management wanted the researchers to do more strategic work. The decentralized, anything-goes model could handle higher volumes of testing, but it also created a high risk of self-confirming research, and the quality of research varied tremendously from project to project.

UserTesting created a hybrid model that empowers non-researchers to test, but within guidelines and processes that make it more uniform and efficient. The key elements of the new process include:

- The designers have been trained, and are required, to conduct their own evaluative tests. The VP of design requires tests at key stages in the development process, especially discovery and prototype validation. A project cannot proceed unless the testing is done.

- All testing projects have to be approved by a steering committee that meets daily. There’s a formal research request form, and when the request is approved it’s added to a central testing queue stored in Monday.com. During approval, the committee decides whether a project will be managed by a designer, product manager, or researcher.

- The researchers are divided into two roles: Evaluative researchers who partner closely with the designers to supervise and assist their testing, and strategic researchers who partner closely with director-level product managers to assist in their strategic planning.

The new process is still evolving, but already there has been a substantial increase in testing, and the product managers are delighted to have a research thought partner embedded with them to help make better-informed decisions.

You can read two detailed interviews on the UserTesting process, with many more details:

- An interview with UT’s VP of Design on how the new process works (link)

- An interview with a product management director and strategic researcher on how they work together in the new system (link)

Conclusion: The path is clear

Scaled human insight is a new practice, and companies are still learning how to use it fully. But already some lessons are clear:

- Scaled insight pays off. Companies are already seeing tangible benefits from it, in the form of reduced rework, faster implementation, and more satisfied customers. Because of these benefits, even companies that initially struggled to scale insight have usually replanned and tried again rather than giving up.

- One size fits one. The scaling program needs to be adapted to a company’s management and decision-making culture. What works best in one company may be completely off base in another.

- It’s a journey. Like other major business processes, scaling insight is never finished. You should plan to evolve and optimize it over time.

- It works best when you commit to it. Companies that have a strong executive commitment to scaling insight, and allocate resources to support it, are far more likely to succeed. The companies that struggled usually approached the transition casually and assumed that any problems would solve themselves. Wishing is great in Disney movies, but to scale human insight you need a plan and commitment.

Additional resources

Here are some articles and links where you can learn more:

- How to scale user feedback, a 90-minute webinar with UserTesting and consultant Flywheel Strategy

- Ki Aguero on democratizing experience research at Ford

- Ann Hsieh on scaling insights with a tiny research team

- Design guru James Lane on democratizing design (starts just after the halfway part of his interview)

- Simon Mateljean on scaling insights to the entire design team

- Jen Cardello of Fidelity on scaling user research in an agile development team

- How UserTesting built experience research into its product development

- Nielsen Norman Group on democratizing research

Photo by RUN 4 FFWPU

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of UserTesting or its affiliates.

Table of contents

- Why companies care about scaling insight

- How to make scaling work

- Four steps to scale scale human insight

- Step 1: Agree on the goals for scaled insight, and create a plan to roll it out

- Step 2: Decide how you’ll control the quality of the tests

- Step 3: Drive adoption by non-researchers

- Step 4: Transform the role of the research team

- Conclusion: The path is clear

- Additional resources